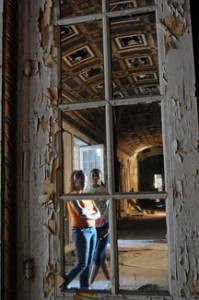

Largely due to new laws, cleanup efforts and a diminished population, the number of children in Detroit with elevated lead levels has fallen dramatically over the past several years. Photo: Bridgette Wynn.

DETROIT — When Renee Thomas moved into her two-story home two years ago, she had no idea it posed a hidden threat to her four children.

But a new city law forced her landlord to check the century-old house for lead contamination. Old, deteriorating paint had left lead dust on its windows, floors and porch. Through a patchwork of grants and city partnerships, the contamination was cleaned up.

Renee Thomas’ rental home in Detroit was contaminated with lead dust until a new city law forced the landlord to have it checked, cleaned and repaired. Photo: Brian Bienkowski.

“They kept cleaning the floors … cleaning them over and over again,” Thomas said. “It was in the windows, in the doors and on the railing going upstairs. They replaced all of that.”

Armed with new laws, paintbrushes and industrial vacuums, Detroit over the past few years has declared war on the toxic metal that has long plagued its neighborhoods. And it appears to be winning.

The number of Detroit children with lead levels exceeding a newly revised federal guideline has dropped more than 70 percent, from about 10,000 kids to 2,900 since 2004. Experts say a new emphasis on cleanup or demolition of homes, a shrinking population and stricter city landlord laws have spurred the improvement.

Similar drops in lead poisoning have occurred in other Rust Belt cities, including Cleveland, Chicago and Milwaukee.

“Over the past 12 years, there’s been a push to get rapid intervention for kids exposed, abatement in contaminated homes and enforcement for landlords,” said Lyke Thompson, director of Wayne State University’s Center for Urban Studies.

Nevertheless, the number of children with elevated lead levels in Detroit and these other cities remains much higher than the national average, and low-income people of color are most at risk. More than 10 percent of Detroit children 6 years old and younger still exceed a lead guideline set by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last year.

Making matters worse, federal funding for local programs has been slashed, threatening the progress made in Detroit and other cities.

“The problem is slowly going away,” said Robert Scott, an analyst with the Michigan Department of Community Health. “But we want the number to be zero.”

Low levels of lead affect children’s IQs, their ability to pay attention and how well they do in school, according to the CDC. It also has been linked to violent and antisocial behavior.

Old, peeling paint is one of the largest sources of lead in Detroit, where 94 percent of housing was built before 1980.

Old, peeling paint is one of the largest sources of lead in Detroit, where 94 percent of housing was built before 1980. Photo: Flickr, Environmental Health News.

Cities in the industrial Midwest historically have high rates of lead poisoning because they have a lot of old housing built before 1978, when lead was banned in paints. About 94 percent of Detroit’s homes pre-dates 1980, compared with 58 percent nationally, according to the 2010 U.S. Census.

Experts agree that indoor dust is the major source of exposure. But these cities also had lead smelter sites and other factories that generated lead dust. Randy Raymond, a geographic information specialist with Detroit Public Schools, mapped the city’s problem areas for lead and found that most were near former car and battery manufacturing plants. And new research suggests that in the summer, when Detroit children spend more time outdoors, their lead levels spike because contaminated dirt is kicked up by winds and held in the air by humidity.

A coalition of researchers, medical professionals, community organizations and government agencies known as the Detroit Lead Partnership has spearheaded much of the city’s progress in cleaning up lead contamination, Scott said.

Mary Sue Schottenfels, executive director of CLEARCorps, a nonprofit group that kick-started the cleanup of the Thomas home, said her organization and others lobbied for new city laws that now hold landlords accountable for keeping properties lead-free. Under a 2010 law, landlords must check homes built before 1978, and if lead is found, they cannot rent them until they are cleaned up to state standards.

Thompson said population declines and demolishing of older homes also have led to fewer lead-poisoned kids in Detroit. The city’s population has plunged 25 percent since 2000, and its rental vacancy rate is about 19 percent. In addition, under Mayor Dave Bing, the city has demolished 6,700 vacant homes and buildings in the past three years.

“Basically in a shrinking city, less children are getting exposed,” Thompson said.

No safe levels

More of Detroit’s housing is vacant, which has reduced the number of children living in old, contaminated homes, experts say. Photo: Brian Bienkowski.

Last October, the CDC cut its guideline for lead in half, to 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood, in response to mounting scientific evidence that low levels can harm children’s developing brains.

Under the new health guideline, 10.2 percent of Detroit children age 6 and younger had excessive lead levels in 2011, compared with 33.3 percent in 2004 that exceeded that level, according to data from the Michigan Department of Community Health. For Cleveland, it’s 17.6 percent of children, and for Milwaukee, 12.9 percent.

All those percentages remain much higher than the national average — 5.8 percent in 2011.

Nevertheless, Detroit now has 70 percent fewer kids with lead levels considered unhealthful. Based on the previous CDC guideline, the improvement was even greater — more than a 90-percent decline between 2004 and 2011.

Researchers and medical professionals applauded the lowering of the federal threshold. But they say it may not be low enough.

“Scientifically, there is no safe level of lead exposure,” said Dr. Bruce Lanphear, a professor at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, who specializes in childhood exposures to lead and other toxics that affect the brain.

Elevated lead levels have been linked to lower test scores among Detroit students. Photo: USAG-Humphreys.

It appears that impacts of lead occur even at blood levels below 2 micrograms per deciliter, Lanphear said.

Also, exposure to low levels leads to a quicker loss in IQ points, he said. When children’s blood lead levels increased from 2.4 to 10 micrograms per deciliter, IQs dropped by 3.9 points, compared with a 1.1 point drop when levels increased from 20 to 30 micrograms per deciliter, according to a 2005 Lanphear study.

Lead has been linked to poor school performance among Detroit children. City researchers found that children with higher lead levels were more likely to need special education, and, as blood lead levels went up, students’ math, reading and writing scores dropped, according to a 2010 study. Children with blood lead levels as low as 5 micrograms per deciliter also are more likely to be arrested, according to a 2008 study by the University of Cincinnati.

Poorer children consistently have higher levels of lead. But, even controlling for income and other factors, black children still have blood levels 50 percent higher than other races, Lanphear said. Research suggests black children metabolize the metal differently. That magnifies the problem in places such as Detroit, which is 83 percent black.

Funding cuts

Not too long before the CDC adopted a more stringent threshold, the agency severely cut its lead prevention funding, which Detroit and other cities have heavily relied on. In this fiscal year, it was slashed from $30 million to $2 million.

Thompson of Wayne State University said the lack of money has “halted lead services in their tracks” in Detroit.

“The CDC has pulled back big time and at the same time the city is still suffering from the financial crisis, and the tax base is hit because people are leaving,” he said.

Schottenfels said almost all of the money in Detroit to fight lead — about $1 million annually — came from the CDC. “With current funding, the effort to stop this problem is in dire straits,” she said.

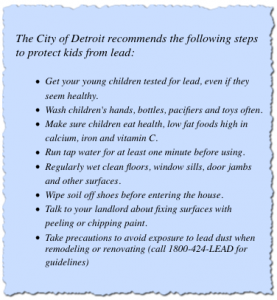

Graphic: Environmental Health News.

Milwaukee is fighting the same battle, said Paul Biedrzycki, director of disease control and environmental health at the Milwaukee Health Department.

“We are trying to do more with less,” Biedrzycki said in an emailed response. He said the department does not currently have the resources to inspect homes of children with elevated lead levels.

Research shows that lead prevention more than pays for itself.

“Each dollar invested in lead paint hazard control results in a return of $17-$221 or a net savings of $181-269 billion,” according to a 2009 study by the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan economic think tank in Washington D.C.

Lanphear said most people point to vaccines as the most cost effective public health spending programs, and their cost benefit ratio is typically $1 spent for every $16 saved.

“So reducing child exposure appears to be more cost beneficial than what we tout as the most cost beneficial program we currently have,” he said.

The benefits of Detroit’s lead prevention work aren’t hard for Renee Thomas to see. Her tidy home stands out in her working class neighborhood with its fresh paint and new porch and windows.

After she moved in, she had all four children, ages 6, 8, 10 and 12, tested for lead. None had elevated levels. But she still keeps a lead prevention pamphlet handy and uses a new vacuum designed to minimize dust.

“I feel much better — now they can play anywhere,” Thomas said

Brian Bienkowski is a former Echo reporter now working for Environmental Health News where this story first appeared.