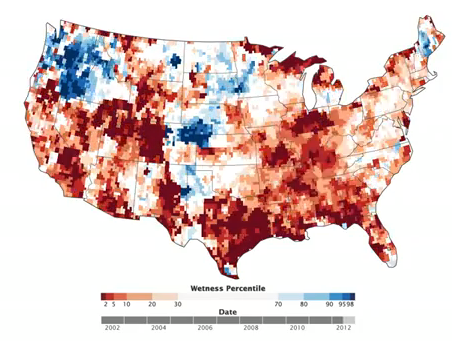

This image shows otherwise unseen consequences of drought.

This image shows otherwise unseen consequences of drought.

But it’s just as fascinating for what it says about the unique characteristics of the Great Lakes region and the challenges of communicating environmental science.

First, the drought: The redder areas show where groundwater — that’s the water underground that you can’t see — is below its long-term average.

The map was created with data gathered by twin NASA satellites launched in 2002. They measure changes in the Earth’s gravity caused by changes in mass near its surface.

Changes in groundwater affect the distribution of that near-surface mass and gravity. Here’s an animation of the changes over time:

Pretty cool, huh?

But what does it say about the uniqueness of the Great Lakes? Note the redness of northern Michigan. This is important because half the people in Michigan get their drinking water not from the Great Lakes but from groundwater.

But why so red in the north and less so elsewhere in Michigan and parts of other Great Lakes states?

Here’s one answer: “For some time now I’ve been concerned that the dryness indicated by our maps in Michigan may be in error,” Matthew Rodell, chief of the hydrological sciences laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, explained in an email.

There are two factors that complicate measuring gravity in the region, Rodell said. One is that changes in lake levels also affect mass. The low resolution of the satellites may mean those influences show up in nearby regions.

Declining water in the Great Lakes influences what the satellites see.

The other factor is something called Glacial Isostatic Adjustment. It refers to how the region is still rebounding from getting squashed by glaciers that retreated roughly 12,000 years ago. Scientists try to remove that influence from their calculations, but the models for doing that are imprecise.

That doesn’t mean the map is necessarily wrong. It may well be right. Federal data indicates dry conditions in the region almost every year since 2003, Rodell said. “It’s certainly possible that the redness in northern Michigan is real.”

This map and how it evolves into greater certainty says a lot about how science works. Scientists do the best they can to explain what they observe. When those explanations change, it’s because they’ve gathered new data or developed new theories.

That complicates the task of those of us who communicate science. The challenges of interpreting the Great Lakes regional data shouldn’t undermine the entire map.

But reporting them can lead some people to question the value of the science that has brought understanding this far.

When NASA began posting these maps last year, Texas was in a major drought but the map showed a wet spot in that state’s panhandle.

“I got feedback from some Texans that bordered on hate mail and I’m not sure they read or understood my explanations,“ Rodell wrote. “We later made some improvements to the processing that largely fixed the problem.”

Maybe the key is to think of science stories more like mystery stories — ones that aren’t always immediately resolved.

That doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy what you learn as the mystery unfolds.

I mean, who would have thought our region is still bouncing back from the glaciers that long ago provided its unique landscape?