In the past five years the amount of algae in Lake Ontario has exploded to levels scientists say were commonplace 25 years ago. That was before phosphorus was controlled in wastewater and detergents.

But the recent resurgence is just in the shallow water close to shore.

In deep water, levels remain within the U.S.-Canada International Joint Commission’s goal of 1 part per billion. Closer to shore, levels skyrocket to as much as seven times as high.

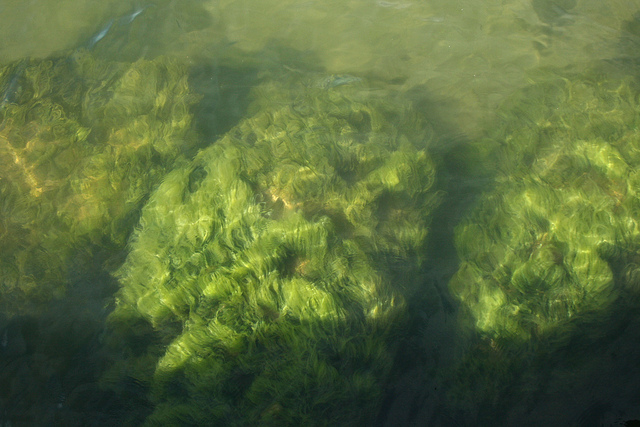

Algae in Lake Ontario sticks close to shore. Photo: birdvoyeur (Flickr)

“We’ve done a good job in Lake Ontario in terms of improving offshore water quality, but in terms of the … lake along the coastline, there are still some issues that need to be understood and dealt with,” said Joe Makarewicz, a professor at the State University of New York’s Borckport College who has studied that nearshore zone.

Nutrients like phosphorus run off land and into the lake with rain and snow. That nutrient-rich water doesn’t immediately mix with the lake water, but gets funneled into currents that run along the shoreline.

And where there’s nutrient-rich water, there’s more algae.

Things are a little different on the Canadian side of the lake where the water from tributaries mixes with cleaner lake water more quickly. That cuts down the amount of algae near the beach.

On the southern, U.S. side, scientists saw cloudy, algae-laden water as far as two miles from shore. On the Canadian side, the water is still clear about a mile from shore, said Todd Howell, an ecologist for the Ontario Ministry of the Environment.

Deep water comes to the shoreline more often on the north side of the lake than the south, Howell said. Such upwellings occur when winds blow warmer surface water out to the deeper lake, so the nutrients in surface water break down faster.

“The cold water comes up to the surface and acts as a dilutant, and that makes a big difference,” Howell said. “There’s just greater onshore, offshore circulation on the Canadian side.”

That circulation keeps algae at bay.

“In general, lake currents move parallel to the shoreline, water doesn’t just automatically mix offshore,” Howell said. “That’s what’s happening on the American side.”

Cladophora, a non-toxic algae that often causes beach closings because it stinks, is a particular problem for Lake Ontario.

It is an obnoxious algae, said Scott Higgins, research scientist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada. It can get “so thick you can’t drive a boat with a 100-horsepower engine through it. It washes up on shores and smells like sewage.”

Higgins studied the urban influences of cladophora blooms on Lake Ontario and found that phosphorus isn’t the only culprit. Quagga and zebra mussels may also play a role.

The mussels ingest nutrients and cycle them back into the shoreline ecosystem so they take longer to mix with deeper water, Higgins said.

Changing how land is used can prevent excessive algae on a small scale. Phosphorus can come from direct sources like sewage treatment plants, or indirect sources like fertilizer and agriculture.

Farms with lots of livestock could be a major source of phosphorus loading. Makarewicz said. Such operations can contribute as much phosphorus and nitrogen as a small city and aren’t as regulated as other polluters.

But there are ways around the problem. Nutrient cycling is natural, and Makarewicz said agriculture, fertilizer use and sewage treatment can be done without affecting the watershed.

“The problem is when we don’t do it properly and it leaks out of the watershed and into the streams and into the lake,” Makarewicz said. “I think the future is heading in the right direction, but it’s going to take time.”