Great Lakes waves drive surfboards, kayaks and swimmers. Now they may soon power your computer, television and lights.

Lake Erie waves like this one near Ashtabula, Ohio could provide electricity for homes, businesses. Photo: kuddlyteddybear2004 (Flickr)

The nPower Wave Energy Converter, developed by Cleveland-based Tremont Electric, LLC, moves a magnet and induction coil by each other to generate pulses of current. The company proposes to drop converters into anchored buoys in Lake Erie and let the waves bounce them around.

The movement would generate power and route it back to the power grid on land.

The converters emit none of the carbon that contributes to climate change. That’s in contrast to the carbon emitted by the coal that generates approximately 90 percent of Ohio’s energy, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“With the converter, we’re not trying to push the bounds of new technology,” said Aaron LeMieux inventor of the wave converter and founder and CEO of Tremont Electric. “The converter takes power from things that move, and we get power onshore through a cable system … same as offshore wind turbine farms.”

Converting wave movement to energy is a new field. There are projects in the oceans using similar technology, but Tremont Electric is partnering with researchers to see if it will work in the Great Lakes.

The first research step is to see how dense the waves are and determine how much energy they could produce, said Ethan Kubatko, assistant professor in civil and environmental engineering and geodetic science at Ohio State University.

Kubatko will also explore if parts of the lake are better suited for wave energy. He doesn’t know of any similar projects in the Great Lakes and wouldn’t guess whether or not the technology may be successful.

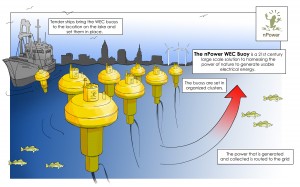

The buoys would be placed in offshore farms and the power would be routed back to the power grid onshore. Drawing: Keary Knerem

The wave converter is a scaled-up version of the company’s personal generator that bounces around in a purse or pocket to produce energy. It powers up electronic devices like cell phones.

But the wave converters are the size of a car and will need to be conspicuously placed in “farms” to generate energy.

LeMieux estimates the farms will take up the area of a “couple of football fields.” He expects six converters per acre. In the ocean, each converter could power around 20 homes, he said. But with less wave density in the Great Lakes, the power generated would be lower.

Offshore wind farms are criticized for ruining the beauty of lakes and their surroundings. LeMieux acknowledges this may be a hurdle with the converters.

“Anytime you deal with the public there’s potential for backlash,” LeMieux said. “But we feel like we’re in a good place where we’ve mitigated a lot of negatives.”

View-seeking residents aside, anglers may not like giant buoy farms in the water either. LeMieux said they “expect but haven’t proved” the buoys could be artificial reefs that improve fishing.

Those engaged in Ohio’s alternative energy landscape said Tremont might face challenges.

“There’s a whole host of issues when you go out into the lake,” said Bill Spratley, executive director of Green Energy Ohio.

Buoys would be anchored to the bottom of the lake and a transfer hub would collect the power from each. Drawing: Keary Knerem

Spratley’s experience has been with offshore wind projects, and he points to public opinion and the regulating and permit structure as the two biggest hurdles.

“But buoys are much smaller than wind turbines,” Spratley said. “You may eliminate some of the aesthetic concerns.”

LeMieux thinks Lake Erie is perfect to test the wave energy converters.

“It’s close … it’s state, not federal waters,” LeMieux said. “We don’t have large sea mammals. No one wants to be the company to bounce a buoy off a sea mammal’s head.”

The permitting process is easier at the state level, LeMieux said. The company will need submerged land leases, which are regulated by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

While Tremont would like to go global with the wave energy converters, the Great Lakes are well suited for kicking off research and development, LeMieux said. And with a state requirement that 12.5 percent of all electricity sold in 2025 comes from renewable energy sources, Ohio may prove a perfect state for the converter-filled buoys.

And with the personal energy generator as a small prototype, wave energy converters are getting attention.

“A few years ago, we were educating legislators,” LeMieux said. “Now we’re getting more traction, and we can put the small scale converter in their hand and they can understand the potential.”