A Michigan State Police Underwater Recovery Unit diver helps document and photograph the Cornelia B. Windiate shipwreck in Lake Huron. Photo: Randy Parros.

It’s all part of the job for some Michigan State Police troopers – writing tickets, investigating crimes and combating loot-stealing shipwreck pirates.

Seventeen Michigan troopers are officers on the road and also divers in the water as part of the department’s Underwater Recovery Unit.

“We dive year-round in all types of environments,” said Trooper Randy Parros, a member since 2002.

The unit receives about 60 to 70 calls each year that range from actual dives to public relations events.

Divers recover bodies and crime weapons. But they also document artifacts and features of Great Lakes shipwrecks.

“A lot of times artifacts get moved around a wreck after divers start visiting,” said Wayne Lusardi, an archaeologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

Troopers get dive practice while providing the help Lusardi needs to document newly discovered shipwrecks, sometimes before recreational divers have ever touched them.

“Our unit would assist the [Department of Natural Resources] with checking shipwrecks in the Great Lakes, videotaping them, making sure to check to see if artifacts are still being left there or if they have the belief that someone has stolen artifacts,” Parros said.

Lusardi has worked with the unit on a dozen projects. Recreational divers often discover undisturbed shipwrecks. The first such project Lusardi and the unit tackled together was in August 2005–they explored the 40-foot schooner, May Queen.

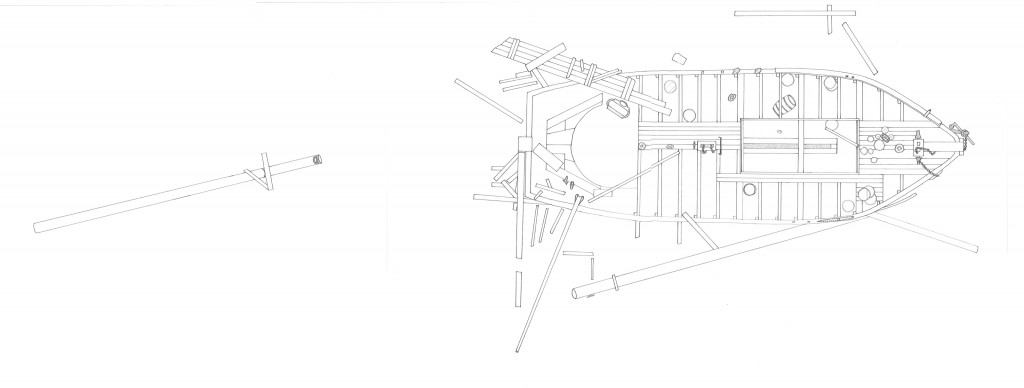

A site plan is drawn to document the location of artifacts on the May Queen, a Great Lakes shipwreck. Drawing: Wayne Lusardi.

Lusardi draws a detailed map–a scaled drawing of the wreck and also the location of objects like pumps, anchors, ceramic objects, cargo materials, personal items and other artifacts.

He evaluates the wreck for deterioration. Waves and sand increase deterioration in wrecks near the shore. Vessels in deeper waters are damaged by organisms like zebra mussels.

The unit takes photographs and video footage and catalogs artifacts based on their condition.

Documentation not only helps identify when artifacts have been moved or gone missing–measurements from the May Queen helped historians to identify it.

The May Queen was built in Marinette, a suburb of Menekaunee, Wisc. in 1875. It sprung a leak and sunk with a cargo of salted fish near Menomonee, Wisc. in December 1882, according to a Wisconsin Underwater Archaeology Association publication.

“It was a really neat project to be able to be one of the first divers to this site and report the artifacts,” Lusardi said.

Other times, the team dives to find new wreckage. The underwater recovery unit is credited with discovery of the schooner William Young under 120 feet of water in the Straits of Mackinac. The team was using sonar to search for a body and found the shipwreck by accident, Parros said.

Stolen artifacts are often reported by diving charters, said Trooper Jeff Miazga, a 12-year unit member. Ship wheels and capstans, which bear the ship’s name, are prized items.

“That’s what these shipwreck pirates are looking for…it definitely adds value,” he said.

Artifacts from the May Queen shipwreck, including lanterns, ceramic plates and pitchers among other items. Photo: Kim Brungraber.

Bells, lanterns, ceramic pieces, glass bottles and parts of the ship’s rigging, such as deadeyes and pulleys, have also gone missing, Lusardi said.

Stiff fines and jail time accompany removal of shipwreck artifacts within the state of Michigan. Punishment ranges from 93 days to 10 years in jail or $500 to $15,000 in fines, depending on the value of the artifact and if it is a repeat violation, said Tiffany Brown, a Michigan State Police public affairs specialist.

But shipwreck thefts are uncommon now that laws prohibit the taking of artifacts, Lusardi said.

“It used to be back in the early days of scuba diving around the Great Lakes, it wasn’t really clear to divers who owned what so they were more apt to take things from shipwrecks,” he said.

New technology is changing the game.

“Now we can use electronics,” Mizaga said. “We’re doing more now with less divers than we’ve ever done.”

Better camera equipment, underwater robotic vehicles and sonar help the team look for shipwrecks or accidents and increase their success at finding them.

Sonar was used to more quickly locate the underwater site of a summer 2010 plane crash in Lake Michigan that claimed four lives, Parros said. Crew members dove 173 feet to recover two victims.

Technology also lowers the risk to divers.

Deep water diving is dangerous. Remotely operated vehicles are used to videotape shipwrecks at around 500 feet.

Troopers work two years on the road before applying for specialty training. In underwater recovery training they learn scuba diving basics in a pool or swim tank in Lansing, Mich. for one week. They undergo an additional one-month training course with dives in different water types, including water with low to no visibility–a common quality of sites like the Saginaw and Flint Rivers.

Diving gives troopers diverse experiences, from giving families closure when a body is found to solving crimes and identifying shipwrecks.

“It’s a break from my everyday job,” Miazga said.