Before the Columbian Exposition in 1893, Chicago’s plan to pipe water from the famous springs of Waukesha, Wisc. 100 miles to the north led to an armed skirmish as townspeople turned out to defend their famously “pure,” medicinal waters.

Before the Columbian Exposition in 1893, Chicago’s plan to pipe water from the famous springs of Waukesha, Wisc. 100 miles to the north led to an armed skirmish as townspeople turned out to defend their famously “pure,” medicinal waters.

A century later, the tables are turned.

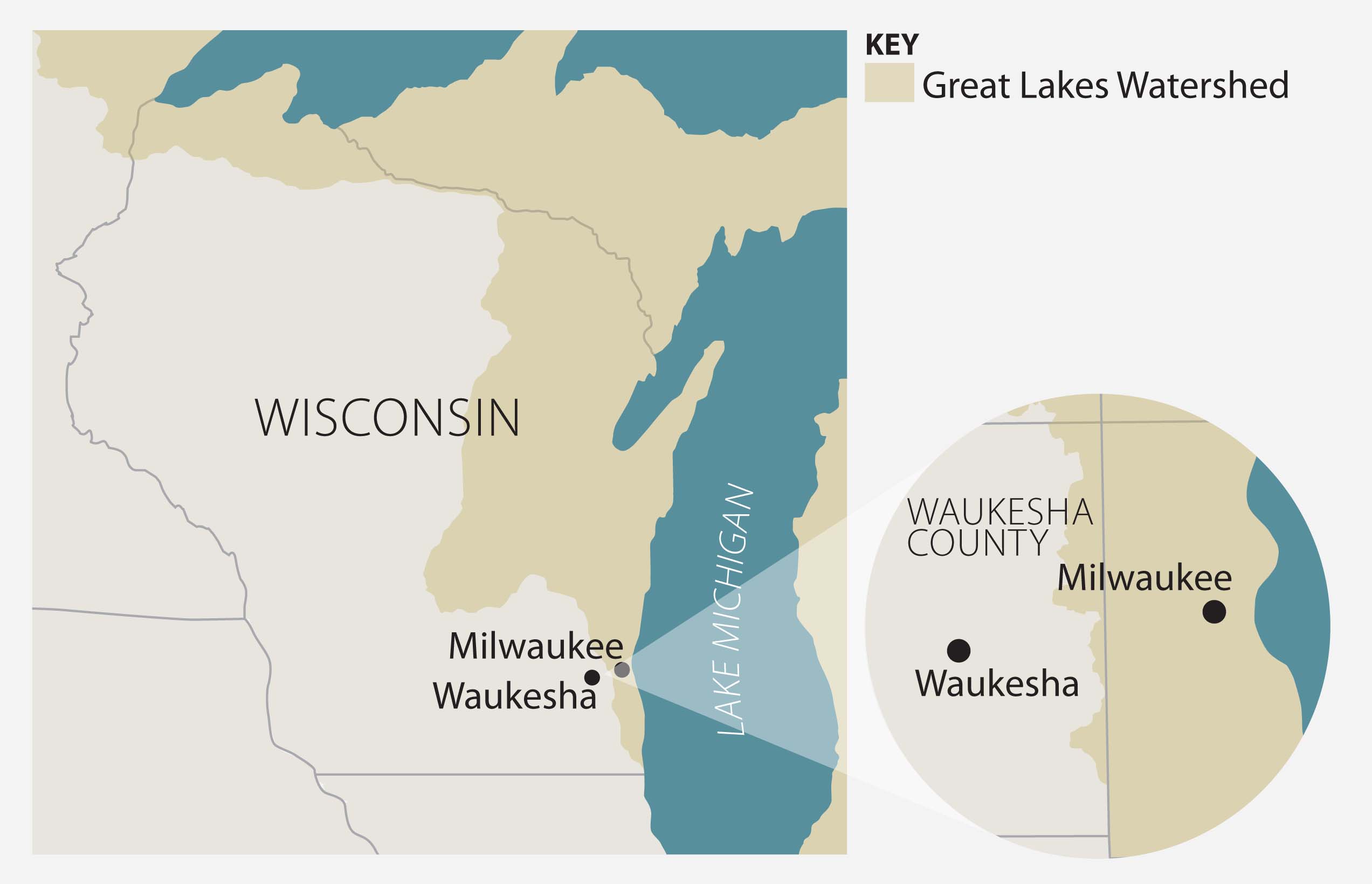

It turns out Waukesha’s deep wells are contaminated with naturally-occurring radium, with concentrations increasing as the water table drops five to nine feet each year. So for years Waukesha has sought to tap the water of Lake Michigan 18 miles to the east. But the city of about 68,000 people lies outside the Great Lakes basin, a mile and a half west of the divide where surface water flows into either Lake Michigan or the Mississippi River.

Waukesha was a make-or-break test case during the years-long drafting of the 2008 Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact — the landmark agreement banning almost all diversions of Great Lakes water out of the basin.

Case sets precedence for weighing diversions

Two years later, the city continues a complicated struggle for approval from the eight Great Lakes governors to use — and return — Lake Michigan water.

It could be months or even years before a decision is made. But Great Lakes advocates say the process already indicates that the Compact is doing what it was meant to do.

“Waukesha, Waukesha,” muses Noah Hall, author of the Great Lakes Law blog and a professor at Wayne State University law school. “When we were drafting and negotiating the Compact, it was very clear that if the Compact made it impossible for Waukesha to divert water it wasn’t going to pass; and if it made it too easy it wasn’t going to pass. What people wanted was exactly what I think we got: a very, very little open window to give Waukesha some possibility of getting a Great Lakes diversion, but it won’t be easy and it shouldn’t be easy.”

Weighing options

One of the alternatives to be considered is getting water from Wisconsin's Fox River. Photo by Cimexus via Flickr

To use Lake Michigan water, Waukesha must prove it has no other “reasonable” source of water to replace that from the radium-laced wells. Radium is linked to increased cancer risk, and the federal government has ordered the city to find a safer water source by 2018.

Among the alternatives: Decontaminate the water enough for public use, get it from the Fox River, pump shallower water without radium or buy it from another municipality outside the Great Lakes basin. These options are expensive and pose various logistical hurdles. After weighing public health, environmental impact, sustainability and feasibility, the city’s application concludes that Lake Michigan is the “only reasonable water supply.”

If it does get approval, Waukesha will have to negotiate a plan to buy water from Racine, Milwaukee or Oak Creek, which already have intake structures in the lake.

Even returning the water presents hurdles

The Compact also mandates that Waukesha return the water it uses to Lake Michigan, minus an amount considered “consumptive use.” This could be by piping treated wastewater back to the lake, piping untreated water to Milwaukee’s treatment plant or emptying treated wastewater into a river or stream that flows to Lake Michigan. The city’s application, submitted to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources in June, says that the cheapest and most feasible option is returning the water through Underwood Creek. But this water — which even treated has significant levels of suspended solids, bacteria, phosphorus and other compounds — would have ecological impacts on any waterway it enters.

“How you send it back is a key issue,” said Dave Ullrich, executive director of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative. “You’d be putting a fairly significant volume of water from Waukesha into a small river that has seasonal variations.”

A high bar

The Wisconsin DNR must approve the proposal before it goes to the council of eight Great Lakes governors for a vote. They must approve it unanimously for Waukesha to get the water. The DNR has said Waukesha’s application to tap up to 10.9 million gallons a day is incomplete, and the agency won’t consider it until revisions are made.

A Nov. 18 public meeting where the WDNR was to explain these shortcomings was canceled at Waukesha officials’ request. They objected to the likely presence of environmental groups observing the process.

“The bar for approval for a diversion is extraordinarily high, and purposely so,” said Joel Brammeier, president of the Alliance for the Great Lakes. “Being able to divert Great Lakes water is an extraordinary privilege — there’s a very steep hill for any community to climb before that privilege is granted.”

Waukesha’s application says the city has reduced its water use through conservation started in 2006. But it says that’s not enough. It argues that while the city lies outside the surface watershed of Lake Michigan, it is solidly within the area where groundwater flows to the lake. That’s true, but the Compact was written based on surface watersheds, Hall says. Groundwater is less relevant since it typically does not have a direct connection to the lake.

Diversion fuels sprawl fears

Meanwhile the application also calls for extending Waukesha’s water service area by about 80 percent, which has riled residents of surrounding rural areas who envision being overtaken by sprawl. The expansion would encompass the adjacent town of Waukesha, distinct from the city of Waukesha, which gets its water from shallower uncontaminated wells. This implies the city intends to annex the town, which many town residents stridently oppose.

Given Waukesha’s persistence, Great Lakes advocates say vigilance is needed to make sure the the Compact is thoroughly enforced. (The Waukesha mayor’s office did not return calls for this story).

“The states need to be strict early on to set precedent, because over time there will be efforts to chip away at the requirements,” Ullrich said.

“My hope for Waukesha, regardless of whether (the request) gets approved, is that the region comes out on the other side knowing the Compact is working,” Brammeier added. “If we get that out of the process, we’ll be in better shape than before Compact existed. If we sidestep the Compact, if Waukesha tries to find ways to sneak around provisions that were designed to protect Great Lakes water, then we’ll have a problem.”