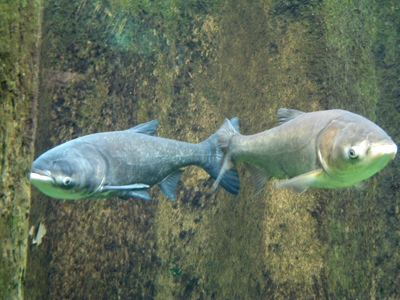

Fishermen found a bighead carp in Lake Calumet, well past the electric barrier designed to stop invasive fish. Photo: Peter Haugen

Past dispatches on the onward march of Asian carp into the Great Lakes have always come with panic-curbing caveats that the worst nightmares of those depending on the $7 billion Great Lakes fishery had not yet come true.

Even after biologists discovered Asian carp DNA past the fish-shocking barrier in November and a poisoned carp below it in December, officials stressed that no surveys had exposed live fish on the wrong side of the barrier.

Now commercial fishermen have pulled a live, 20-pound bighead carp from Lake Calumet, 30 miles past the barrier and six unimpeded miles away from Lake Michigan. This once again begs the question:

Can we panic now?

“The answer is no,” said Andy Buchsbaum, director of the National Wildlife Federation’s Great Lakes office.

By all indications, not enough Asian carp are in the canal system to establish a breeding population there or in Lake Michigan, he said. “As long as that’s true, we do have that time.”

The Great Lakes Sport Fishing Council is also calling for level heads.

“Don’t ever panic,” said council president Dan Thomas. “You never panic under stress because then you lose control of rationality and strategic thinking.”

Not everyone is even convinced that the carp living in Lake Calumet swam past the barrier to get there. It may have had some human help, said Gerald Smith, curator emeritus of fishes at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Zoology.

“Somebody – fishermen, mischievous teenagers, whatever – is releasing these things because they’re so readily available in the Illinois River right there,” Smith said. Carp discovered in several Chicago-area ponds were likely planted there by humans, he said.

Biologists will test the captive carp’s DNA to determine where it came from, said Thomas.

“If it’s a natural fish that evolved through growth and movement from the Mississippi, there’s cause for concern,” he said. “There could be others.”

Natural or not, Buchsbaum said finding a live fish underscores the need for urgent action on a physical barrier between the Mississippi and Lake Michigan basins.

But urgent action is hard to come by.

The Army Corps of Engineers say they need three years to study the feasibility of a barrier before they can build it, Buchsbaum said.

“That’s just much, much too long,” he said. “We need them to finish the study and get working on putting the barrier in.”

The fishing council’s Thomas is also frustrated with the Corps’ plodding bureaucracy. But he’s just plain had it with Congress, particularly politicians who have postured on closing the locks in Chicago but have let bills die that would bolster ship ballast water regulations against invasive species.

“I can’t begin to tell you how angry I am with them,” he said. “When you take an oath before God that you will do something, and then you violate that oath, God should have struck you dead right on the spot.”