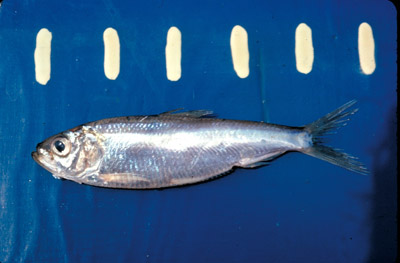

Alewives were once a nuisance non-native species in the Great Lakes. Now they prop up the lakes' hugely profitable salmon fishery. But some experts say they've still got to go. Photo: David Jude

By Jeff Gillies, jeffgillies@gmail.com

Great Lakes Echo

Sept. 2, 2009

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories about the challenges of managing non-native fish in the Great Lakes.

Fishery managers have made little progress in restoring lake trout, the Great Lakes’ dominant predator until the species collapsed in the 1940s and 1950s.

Most of them agree that alewives, a non-native fish, are a big part of the problem. They invaded the lakes from the Atlantic Ocean after the Welland Canal opened in 1932. Alewives eat young lake trout and disrupt chemical processes important to their reproduction.

But biologists don’t plan on getting rid of them now that they’re here. Instead, Lake Michigan managers recently launched fish stocking strategies that protect alewives.

What’s going on?

Invasive species are usually the target of disdain and eradication programs. But alewives get a pass because they’re the main food source for two other non-native species – the chinook and coho salmon. And those salmon are cornerstones of a multi-billion dollar Great Lakes fishery.

Though states imported salmon to control alewives, management plans now serve to keep enough alewives around to keep salmon healthy and abundant.

And as long as state agencies aim to keep available lots of alewives for salmon to eat, lake trout rehabilitation is impossible, said Mark Ebener, an assessment biologist with the Chippewa Ottawa Resources Authority, a regulatory agency representing five Michigan Indian tribes.

Other experts disagree.

Great Lakes fisheries managers have no plans to abandon the profitable salmon fishery, said Marc Gaden, spokesperson for the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

“There’s no inherent contradiction between managing for the native fishery, and also stocking fish for recreational purposes,” he said. “There is definitely a balance that needs to occur.”

Until the mid 1900s, lake trout were the top predators in every Great Lake but Erie. They supported tribal and commercial fisheries. But a slew of factors drove them nearly extinct in all of the lakes but Superior.

Between overfishing and the invasion of the parasitic sea lamprey that feasted on the fish, the Great Lakes’ annual lake trout harvest plummeted from 15 million pounds to 300,000 pounds by the 1960s.

Great Lakes fishery managers have tried to restore lake trout through sea lamprey control and planting young fish. That’s only worked in Lake Superior where a small lake trout population remained after the species’ basin-wide collapse.

Some researchers think lake trout restoration hasn’t worked because fisheries managers have stocked the wrong age fish in the wrong places at the wrong times.

Others, like Ebener, say the biggest problem is the 6-inch alewife. They exploded by the 1950s and 1960s because there weren’t enough lake trout left to control them. They crowded out native species like white fish and perch, and were prone to huge die-offs that would cover beaches with rotting fish.

In the 1960s, Michigan managers hatched a plan to control alewives by stocking the Great Lakes with chinook and coho salmon, both native to the Pacific Ocean. The salmon would sit in for lake trout at the top of the food chain and draw recreational anglers looking for a fish that fights.

The plan worked, driving down alewives and creating a world-class salmon fishery better than it was in the Pacific where those fish were from, Ebener said.

That built new interest in fishing for other species. Recreational fishing on the Great Lakes was minuscule before the 1960s, Dexter said. There was no Clean Water Act to keep people and industries from freely polluting the lakes, and anglers were happy to stay inland.

“People just didn’t go out there because the lakes were a dumping ground for everybody,” said Jim Dexter, Dexter, Lake Michigan basin coordinator for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “It was putrid out there.”

But Great Lakes sport fishing grew, bringing a financial boom to sleepy towns that built local economies catering to recreational anglers.

“From guys selling boats to people selling bait to people renting motels, that whole economy developed around salmon,” Ebener said.

Some sports fishermen are worried that state agencies a bias for native species and will pull the plug on salmon, said Dan Thomas, president of the Great Lakes Sports Fishing Council.

“We didn’t create this fishery, they did,” Thomas said. “Now they would take it away from the sportsmen, and the multi-billion dollar economy that it has created,” he said.