By Rachel Lewis

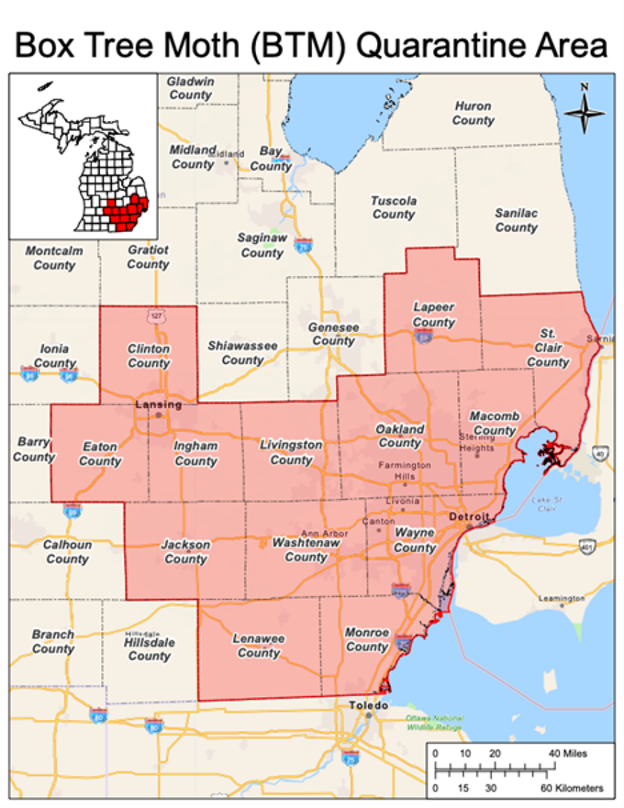

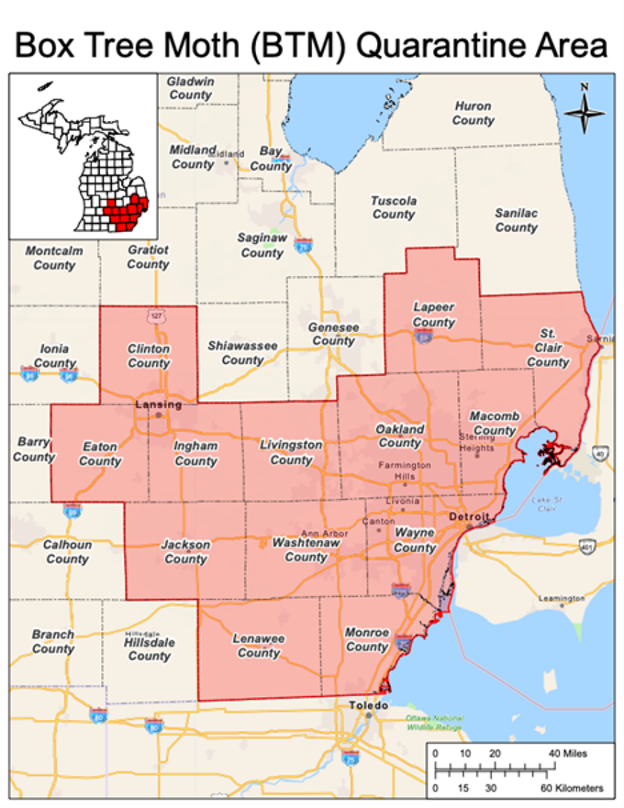

Boxwood shrubs are popular in Michigan because they add greenery in winter months and deer don’t eat them. They had no predators until 2021, when the box tree moth was discovered in New York. Quarantine areas have grown from 11 to 13 counties in Michigan over the last two years.

By Emilio Perez Ibarguen

Homeowners and environmental groups are pushing for reforms to restrict

wake boats to deeper areas far from shore, aligning Michigan law with existing guidance from the

Department of Natural Resources. A handful of states including Maine, Vermont and Tennessee in recent years have passed laws limiting wakeboarding to specific areas or deeper waters, while a push to do so in Michigan last year was dead in the water in Lansing. Wake boat enthusiasts say they’re being scapegoated for a larger problem.

By Clara Lincolnhol

Michigan experiences hundreds of thousands of lightning strikes each year and ranks 25th in lightning density per square mile, according to data from last year. Lightning strikes in Michigan are on the lower side of the scale because the state gets fewer storms than many others. But the number of people struck by lightning in the state is disproportionately high.

By Clara Lincolnhol

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is asking state residents to report the number of wild turkeys they see this summer. The statewide survey will be used to get a sense of the turkey population to find out if baby turkeys are replacing adults. The survey, which runs through the end of August, asks residents to report when and where they’ve seen the birds in Michigan.

More Headlines