A University of Michigan ecosystem scientist uses art to communicate environmental issues to the wider public.

A University of Michigan ecosystem scientist uses art to communicate environmental issues to the wider public.

Sara Adlerstein González, 60, studies aquatic ecology at the university’s School of Natural Resources. She is displaying some of her work at an art show called Water Blues through the end of December.

The show has a double meaning, according to Adlerstein. The shades of blue utilized in the art represent the beauty of the Great Lakes but also the love, melancholy and sadness of blues music and environmental degradation.

It is free and available for public viewing at the “Art and Environment Gallery” of the Dana Building in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The scientist has studied spatial and temporal changes in zooplankton and bottom-dwelling organisms across the Great Lakes, the distribution of lamprey larvae and freshwater mussels in Michigan rivers and the effects of zebra mussels on fish population in Lake Huron and Saginaw Bay.

In this interview, she explains her passion for art.

Q: You said that you use art to communicate issues to a wider audience. What can art communicate about the environment?

A: “I don’t want to believe that my art is going to change the world. But I do think that art and the artist are a part of this world and need to be a mirror of what’s going on and reflect on reality. At this point in time, I think society has big problems with environmental issues. I happen to be a scientist working on the Great Lakes and understanding…stressors in their environment and the role that humans play.”

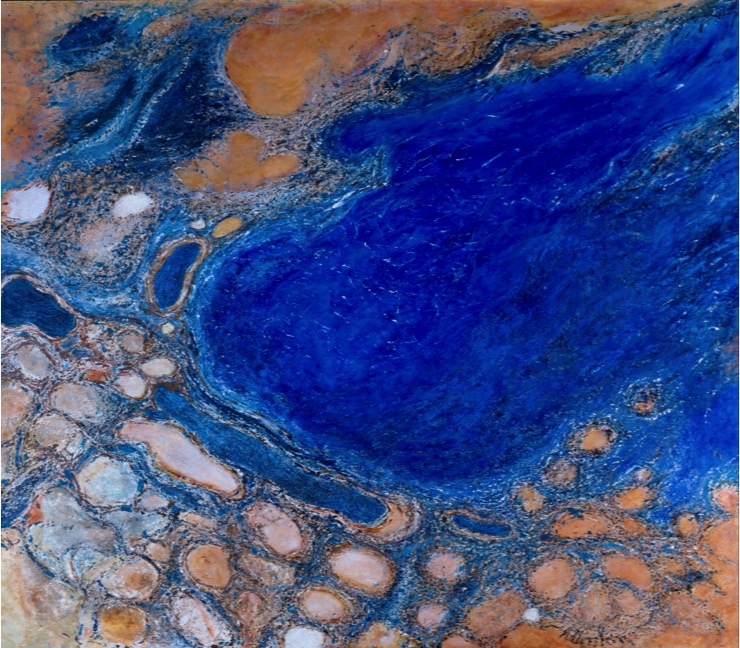

“Headwaters” by Sara Adlerstein Gonzalez.

“I think that the minimum I can do as an artist is open the conversation. To give people a common language, to start with a conversation that might lead to a further interest in getting informed about things. I cannot tell you everything I can write in a (scientific) paper. Who’s going to read that paper? Only my colleagues. While the paintings are going to go around to a different audience…(one) that needs to think about their role in nature. So I think, with my work, I can start the conversation. And give some information to people in a different way.”

Q: When you sit down to create a new painting, where do the ideas come from?

A: “I live for the art. I just sit there and it’s like starting a conversation with you. I don’t wait for an hour to think about what we’re going to talk (about). The conversation just starts and it develops. So it’s very organic, intuitive. I have no filter. So whatever is happening is happening. It’s so direct and connected to what I do everyday, that whatever happens has a connection with either what I’m doing in work or (in) personal life. Everything goes in there and kind of takes its own shape. Most of the time I don’t recognize what’s going on until the piece is done.”

Q: Are there any particular techniques or materials you use?

A: “Every painting is like an experiment. Sometimes I will do the same thing. Sometimes I try to experiment and see what happens with the new combinations. So every time, that’s how I think about my work. They’re all experiments. And it’s very funny because my (artist) colleagues that have gone through formal training, they come to me and they ask me ‘how do you do this?’”

In addition to paintings, Adlerstein has also experimented with multimedia art.

“If you put together images, sound, words and information, I think people open their hearts in a different way so you can meet their soul, instead of going to the brain.”

One multimedia project incorporated video, music, dance and poetry, she said. It was inspired by the water cycle of the Huron River and the relationship between water and culture.

“Unionids, Threatened and Endangered” by Sara Adlerstein Gonzalez.

“Unionids, Threatened and Endangered” by Sara Adlerstein Gonzalez.

“I know there is a limit to what you can do through art, but I think also it’s a language that can be understood by any people and you can at least get people’s attention and get them interested in finding out by themselves what they can do. For example, if you look at some of the paintings…there’s one that is called ‘Unionids, Threatened and Endangered.’ The painting’s title brings attention to these groups of organisms most people are not familiar with. So at least it generates the question ‘what are unionids?’”

Q: What are unionids?

A: “Ah, see! They’re freshwater mussels and they’re natives to North America, well they’re in other places too, but North America’s where you have the (greatest) number of species.”

Unionids have the evolutionary problem of maintaining their population in a river that flows in one direction, Adlerstein said.

“So you can imagine that these freshwater mussels would not be able to (breed) upstream because all the larvae will be flowing downstream. So how are they maintained in the rivers? Well they have this incredible life history they have developed with a fish host.”

Unionids open their valves to attract curious fish, which may think of the mussel as food, Adlerstein said. They close their valves to trap and drug the fish in order for its larvae to enter its gills. Once the unionid lets go, the fish wakes up and swims away.

“The larvae grow and at some point they fall and they recruit upstream.”

Adlerstein’s abstract style is also apparent in the painting “Baker Con Vida.”

“I was teaching this class in collaboration with a colleague in the engineering school here. We took students all the way to Chilean Patagonia to look at the cases of these dams that have been proposed on these pristine rivers.”

“Baker Con Vida” by Sara Adlerstein Gonzalez.

“Baker Con Vida” by Sara Adlerstein Gonzalez.

“Baker Con Vida” was made to represent the untouched beauty of one of those rivers, she said.

“(Painting) also allows me to talk about dams and hydropower and the conflict of the use of water…all those issues that are part of my teaching and research. Same with the one that’s called “Rivertraps.” So that’s kind of the nightmare. There are so many dams in Michigan. When I came here seven years ago, I just couldn’t believe it. There are no rivers without dams.”

“My nightmare of what could become (of) Chilean Patagonia, a beautiful area with all those rivers, and imagining them with dams like here…that’s what the painting is about.”

Q: Do you think your art also encourages the viewer to engage with science more?

A: “Oh yes. And it has been (the case) with people here at the university in the arts.”

“It’s not that much through the painting itself. It’s more about the conversation that gets started with the art. When we did this collaboration, we actually went to the Huron River with one of my colleagues and collaborators from the arts, it was like a field trip.”

“Rivertraps” by Sara Adlerstein Gonzalez.

“Rivertraps” by Sara Adlerstein Gonzalez.

To inspire her artist colleagues, Adlerstein gave them information on science.

“They took it from there. I think, through my connection with other artists, I’m making a difference in them thinking about their artwork and (having them) communicating something that is more important than maybe, ‘I hate my mother.’ That’s why I have been teaching in the (University of Michigan) art school because I think it’s fine to talk about Shakespeare and it’s fine to talk about ‘I hate my mother’ but I think we should also be infusing the information with environmental aspects and help people to cope with this ‘what do I do?’ So inspire people to make a good difference, not a bad difference. I think it’s one at a time, but it works. I see it every day.”

Adlerstein wants to create a course at the university on communicating science for scientists.

You can see a slideshow of her work below: