By Victoria Witke

New research funded by Wisconsin Sea Grant shows Anishinaabe fire practices shaped today’s Great Lakes ecosystems. The region’s forests never existed and can’t continue to exist without people – or fire.

For centuries, old-growth red and white pine dominated the forests of Minnesota Point and Wisconsin Point, while plants like blueberries and cranberries grew abundantly in the open forest.

Today, few pines grow in the forests. The understory is dense, with young hardwoods like maple and basswood fighting for space below the tree canopy. Poison ivy litters the forest floor.

The cause: The U.S. government took away Indigenous peoples’ rights to manage the land.

“If you look at the big picture, there’s not a centimeter on the surface of the earth that hasn’t been impacted deeply by human choice and action,” Evan Larson, the study’s lead author, said.

“If you look into the past, it turns out that’s always been true, that we have been a fundamental part of these systems forever,” he said.

Larson is a dendrochronologist at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. He studies tree rings.

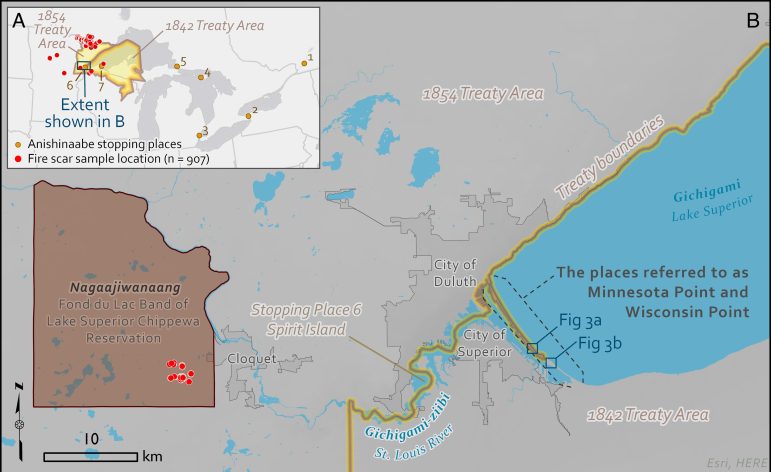

He and the other researchers combined Western science and traditional ecological knowledge to find out how fire was used to manage land in Minnesota Point and Wisconsin Point.

They found fires were intentionally set by Indigenous people to manage the land from around 1756 to 1866.

These fires – called cultural burns – promoted the growth of vegetation, encouraged wildlife habitats and cleared trails for people, among other uses.

Cross sections from stumps, snags and logs paired with small core samples from living trunks show trees were burned more frequently than would happen naturally from events like lightning.

But the study was also “fundamentally structured” by traditional knowledge and stories from the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Larson said.

Larson’s research team included students from the Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College. They engaged with the tribal council and community members of all ages – including a K-12 program.

“In the case of fire, and especially in the Great Lakes, Western science is still catching up to Indigenous knowledge and understanding,” Larson said.

Fire stewardship stopped with colonization, according to the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

That caused red pines to stop regenerating, said Kurt Kipfmueller, a professor at the University of Minnesota who took an advisory role in the study.

Fire cleaned up duff – forest floor debris – which allows pine seeds to germinate in the soil. Without fire, this duff isn’t removed, so seeds struggle to grow.

The flames also killed hardwood saplings, leaving the forest floor open for blueberries and other plants. Now, hardwoods compete for that space.

The forest looks different than it did even at the turn of the 20th century. It’s denser.

Cultural burnings also built wildfire resilience, Kipfmueller said.

These controlled fires would burn up fuel – things like downed trees that catch on fire and spread wildfires.

There’s no stable fire system now, so fuel has built up. Hotter and drier conditions from climate change add to wildfire risk in the Great Lakes, Kipfmueller said.

“If we don’t try to start having some lower intensity burns that are well controlled,” Kipfmueller said, “then we’re just waiting for the inevitable.”

Bazile Minogiizhigaabo Panek is a member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe.

He’s also the fire plan research coordinator for the National Science Foundation-backed Fire Collaborative – a group Kipfmueller and Larson also belong to.

“People are finally realizing that these fires set by Indigenous peoples have been a good way to manage the land,” Panek said. “It’s demonstrated in the tree rings, and it’s demonstrated by the oral knowledge shared by Indigenous peoples that these are the sustainable ways to be in relationship with the land.

“And we’re at a moment where we’re saying, ‘I told you so,’” he said.

Panek hosts “fireside conversations” with Great Lakes tribes. He and his team sit with community members around a campfire, listening to elders share memories about their parents or grandparents using fire. Elders participate in lighting the fires.

Some elders remember picking blueberries as kids with their family, Panek said. After harvesting, they’d light a controlled burn, which helped blueberry bushes flourish again a few years later.

“Memories are brought up within these elders that they haven’t thought about for decades,” Panek said. “You can see them in their minds return to those landscapes and return to that use of fire. And when these memories are brought up, it can be emotional at times.”

For other elders, that listening session was the first time they’d ever started a fire.

Panek said the conversations not only guide his team’s research, but inform natural resource managers on how to integrate Indigenous needs and perspectives into their work, too.

Panek said he’s happy groups like the U.S. Forest Service increasingly collaborate with tribal people.

Still, cultural burns take a long time to organize, he said. Oftentimes, Indigenous groups’ guidelines like when and where burns should take place are not fully listened to by organizers like the Department of Natural Resources.

Panek said he is also disappointed it’s taken this long for Western science and policy to catch up to traditional knowledge.

“Now that people are finally realizing it, Indigenous peoples are at capacity and limited a lot with their time and resources to make this stuff happen,” Panek said. “And we need support from outside entities to make this happen.”