Editor’s note: Reporting for this project was supported by a grant from the Knight Center for Environmental Journalism at Michigan State University.

1st of 2 parts

By Ashley Han and Olivia Watters

Every year, Skyline High School students go salamander hunting.

AP Environmental Sciences (APES) students in this Ann Arbor school have heard too much about the school wetlands’ rare salamanders to not investigate for themselves.

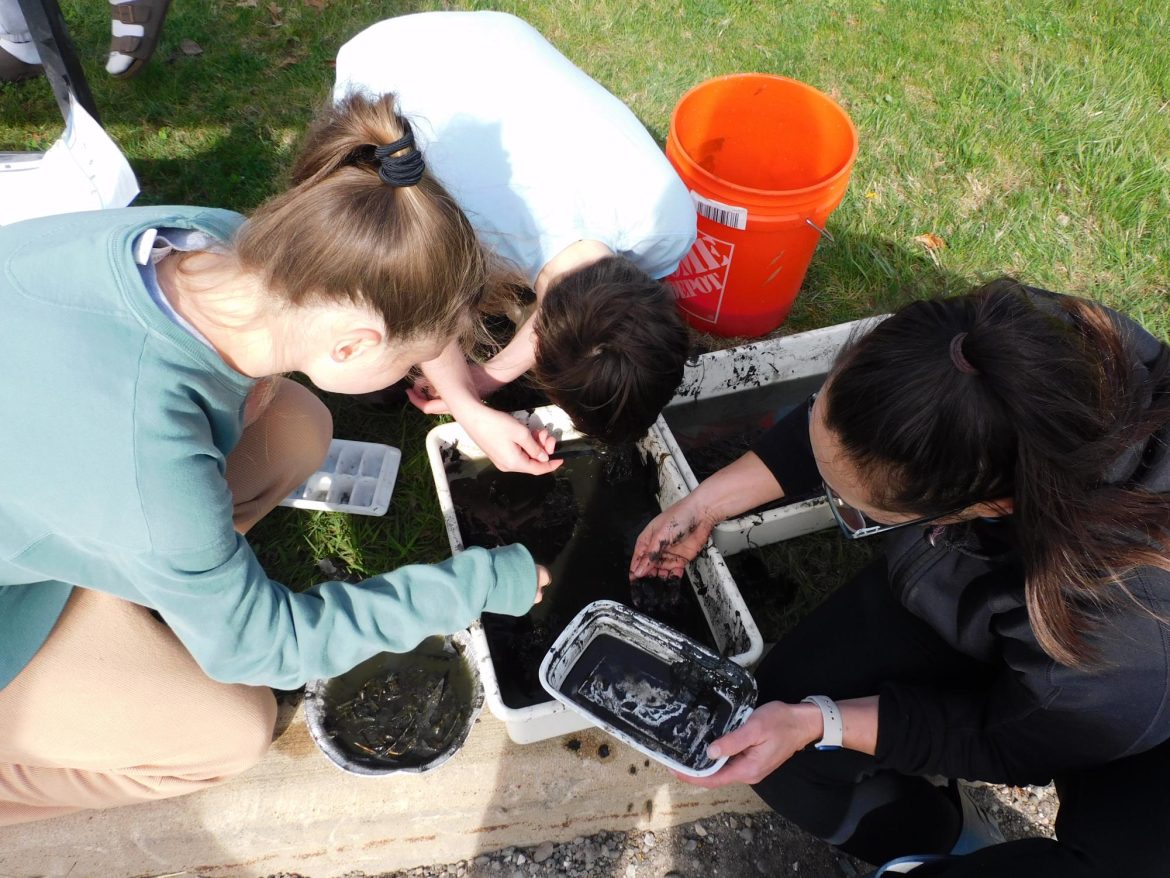

The students, scattered in groups, are armed with nothing more than phone cameras, sketching tools and sharp eyes.

They loop around the school’s woods and wetlands, eyes scouring the ground, dodging poison ivy and flipping over rotten logs in hopes of a glimpse of the rare creatures.

Their assignment is straightforward enough: Create a nature journal, observe the environment and record biotic and abiotic factors.

Yet, there is an unofficial goal: Find the elusive salamanders. Spotting one would be the crown jewel among any other observations.

Nature journals quickly fill up with hasty notes, sketches and photos — food webs, grasshoppers, limestone, black-eyed Susans, coneflowers, deer prints pressed into mud — but rarely a salamander.

“We were told by our APES teachers that there might be salamanders out there because of the fact that Skyline was built where the salamanders used to live. But my groups were never able to find any,” said Elsa Wenzlaff , a former APES student.

“We looked on logs and in the forest near Skyline. And we looked for long periods of time, but mostly just found tiny little bugs,” Wenzlaff said.

The annual search raises more questions than it answers.

“Weren’t these salamanders like an integral part of our community at one point?” Mona Spiteri , another former APES student, wondered aloud. “What happened?”

The Discovery

When construction for Skyline broke ground in 2004, it revealed a rare population of LJJ unisexual hybrid salamanders – first incorrectly thought to be silvery salamanders.

Reports don’t indicate who discovered them.

The habitat supported the only confirmed location for the unisexual hybrids in Michigan during that time.

The salamander finding raised concerns among local families and organizations about the impact of the building on the local salamander population and the health of wetlands.

“The opening of Skyline was actually delayed by a year in part because they found a salamander on the property that they thought might be an endangered species,” said APES teacher Casey Warner.

But it was soon discovered that, due to the salamanders’ unique genetic makeup, they weren’t legally classified as a species and, therefore, weren’t protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Even though they weren’t officially an endangered species, their rarity in Michigan prompted a wave of conservation efforts.

Early Restoration Efforts

In 2005, following a comprehensive report by Ann Arbor’s Division of Natural Area Preservation, an intensive amphibian and reptile rescue was launched.

The city created mitigation wetlands to replace the original one destroyed by construction and intended to provide a new habitat for the approximately 3,000 relocated amphibians, including 200 salamanders.

The effort led to the collection and relocation of over 5,000 individuals, representing 14 species in all life stages.

After the restoration work was completed, the city received five years of funding to study all species on the Skyline wetlands.

The agency’s head herpetologist, David Mifsud, the city’s herpetologist at the time, put together yearly herpetological and wetland survey reports from 2002 to 2007 with a focus on the salamanders.

That included monitoring species to assess the construction’s impact, regular walks along the fence during the first rainfall of spring to collect and relocate salamanders to the new wetland and evaluating how suitable the habitat was for its new residents.

Funding for restoration efforts expired in 2008, and Mifsud also left the project around this time. Since then, there’s been only limited monitoring.

Current State of Skyline’s Natural Areas

Skyline’s natural areas have seen neglect in the last few years.

The black fence installed around the property, meant to protect salamanders from traffic, has seen better days.

“They put that fence up because salamanders were trying to come back to the pond. I’ve heard rumors that they got as far as inside the door,” said George Hammond, a field biologist with the city. “It’s very sad.”

When trees fall on the fence, occasionally students or other volunteers will move the debris, but there’s no money available for proper repairs or maintenance. Many students now simply hop over the crumpled fence to enter the area.

There’s also the water pump that once maintained water levels in a pond for salamanders.

After a tree fell on the pipe connecting it to the well around 2010, it has been inactive and no efforts have been made to repair it.

The 2006 herpetological survey report identified continued monitoring of the Skyline wetlands as “imperative to measure the success of the site” and essential to species survival.

The report recommended that “every possible effort should be made to maximize the education aspects of this site while concurrently being the best stewards of this area. A detailed and comprehensive management plan for this site should be developed, including placement of trails, habitat restoration, environmental education and stewardship opportunities, and long-term monitoring.”

Invasive Issue

The lack of continued monitoring has caused a major invasive species problem.

Invasive, non-native species pose significant threats to ecosystems and biodiversity.

The 2008 herpetology report noted that “treatment is highly recommended to control these species when concentrations are low and control is quite feasible. Management is most critical during the first three to five years of mitigation wetland development, as native plants become established and increase their coverage within the wetlands.”

The invasives that began to grow in 2008 have spun out of control due to a lack of proper management.

Now, non-native plants like honeysuckle, Japanese barberry and autumn olive trees have run rampant. Control has gone from feasible to difficult.

Managing invasive species requires significant resources and ongoing efforts.

Advocates like Warner, the APES teacher, have pushed for Ann Arbor Public Schools to conduct a controlled burn of the area, but efforts have been slow-moving due to lack of funding.

“Anything we could do would be better than nothing,” said Warner.

“I just went in over the summer with a hacksaw and just chopped away at a few [invasives] around the edges, but one person just going in there whenever she has time isn’t going to [do that much], so we really need a burn.”

Warner contacted Mike Appel, a local environmental restoration contractor and owner of Appel Environmental Design, to get an estimate for a controlled burn that could mitigate the invasive species problem.

“Prescribed burns are often challenges to give a price for, as there are many variables,” said Appel. “The interior of the [Skyline] woods in many places is quite nice with few invasive species, while many of the edges show significant encroachment by invasive plants, especially shrubs.”

“Any of the wood’s three edges could also be burned as a smaller section for as low as $1,200,” Appel said.

Ann Arbor Public School’s Involvement

In 2023, Warner received a $400 grant from the school district and the city’s Office of Sustainability and Innovations to buy a wheelbarrow, gloves and mulch to help prevent tree trunks from being damaged by the lawn mowers that mow around Skyline.

The next year, the school district also removed an oak infected with oak wilt from the Skyline woods to prevent the spread of fungus to other trees.

Besides these instances, there is no current ongoing research or maintenance related to the wetlands funded by the district, according to Andrew Cluley, the Ann Arbor Public Schools communications director.

“The district does not have any projects scheduled that are anticipated to impact this area around Skyline” but “remains committed to the environment, including the woodlands and wetlands on the grounds around Skyline High School that are home to salamanders,” Cluely said.

Ashley Han and Olivia Watters are Skyline High School students.