Wind turbines next to a smokestack. Credit: Alfred Grupstra, Pixabay.

By Ruth Thornton

A recent decision by Minnesota’s Public Utilities Commission could mean that wood and trash will be considered “carbon-free” energy sources under the state’s new climate law.

The law, passed in 2023, requires all electricity to come from carbon-free sources by 2040, with interim goals defined for 2030 and 2035. However, it did not define which energy sources meet that definition and instead tasked the PUC to make that decision with public input.

At first glance, the definition of carbon-free energy seems straightforward. But there is disagreement over the details.

More than 60 groups submitted comments to the PUC.

Environmental organizations argued that only those energy sources that do not emit any carbon at all should qualify.

However, other commenters — mainly utilities, municipalities and forestry companies — said energy sources that emit some carbon should be included as long as those emissions are offset by processes that remove an equal amount of carbon over the entire life cycle of the energy source. These fuels are often called “carbon-neutral.”

Public comments pour in

The issue received more public comments than is typical, said Will Nissen, who leads the PUC’s economic analysis unit. “We had a lot of engagement from stakeholders,” he said.

“The commission’s role is basically establishing those criteria and details around how we implement and track progress towards the standards,” Nissen added. “Part of that includes what resources utilities can and can’t use to meet the [carbon-free] standard.”

Nissen said the PUC takes all perspectives into account to make a decision in the public interest.

Instead of making the decision at its September meeting, however, the PUC chose to set up a process to analyze in 2025 the full life-cycle emissions for different electricity sources. The PUC also left open the option of including wood and trash as eligible fuels.

“I wouldn’t say we delayed a decision,” Nissen said. “We’re still in the middle of this proceeding to establish the full range of criteria and guidelines that the commission wants to set to implement the law.”

What counts as clean?

The categories of different energy sources are not always clearly defined.

“There’s renewable energy, there’s clean energy, there’s carbon-free energy, there’s fossil energy, there’s all sorts of different kinds of energy,” said Daniel Bresette, president of the nonprofit Environmental and Energy Study Institute.

Coal and natural gas, both fossil fuels that release carbon dioxide when burned, are the two main energy sources in the U.S., Bresette said. In recent years coal use has been declining while gas power has been increasing.

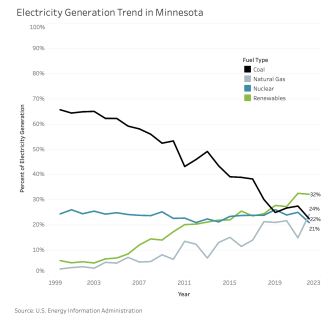

In Minnesota, coal and natural gas each account for almost a quarter of energy generated in 2023.

Electricity Generation Trend in MN

Carbon-free or renewable energy sources generally include wind, solar, hydropower, and geothermal, Bresette said. Together, nearly one-third of Minnesota’s energy came from these sources in 2023, compared to about one-fifth of U.S. energy.

However, not all of them are as reliable as fossil fuels.

“Solar works best during the day, wind resources are typically strongest at night,” Bresette said. “Hydropower is a pretty reliable source, but it requires water.”

Nuclear power is another major electricity source, representing about a fifth of the U.S. energy mix, Bresette said.

Even many of the carbon-free energy sources are not without environmental problems.

Solar panels and batteries to store energy rely on minerals such as lithium, cobalt and nickel, Bresette said. Mining these minerals can cause environmental damage.

“Depending on who you’re talking to,” he said, “there are all sorts of different considerations that go into whether someone evaluates something as clean or carbon-free.”

Bresette stressed that it’s important not only that energy comes from clean sources, but that investments are made in energy efficiency.

Grid reliability

It’s also important not to rely too much on any one energy source, said Zac Ruzycki, director of resource planning with Great River Energy, Minnesota’s second-largest electric provider.

“Having a fuel-diverse portfolio, and really a fuel-diverse grid, is incredibly important,” he said. “There are going to be days when the wind doesn’t blow, the sun doesn’t shine. If you’re putting all your eggs in one basket, you’re really setting yourself up for a hard time.”

Though Great River does not have plans to build a biomass or trash incineration plant, the utility aims to have as many options in energy sources as possible, Ruzycki said.

“Because this is going to be hard, right? It’s not an easy standard to achieve,” he said.

“We’ve got a lot of wind, a lot of resources that would comply, but this isn’t factoring in things like new, large loads that are coming on.”

With new demands on the electric grid, like artificial intelligence data centers and electric vehicles, it’s important to have a flexible energy standard, he said.

He said he is confident that Great River will meet the state’s carbon-free mandate. “We’re on a path to doing that already,” Ruzycki said.

Environmental effects

While proponents of the carbon-neutral argument were pleased by the PUC’s decision, groups such as the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy are concerned.

“We think the law should be interpreted as it was written,” said Barbara Freese, an attorney for the nonprofit group. “And it defines carbon-free as a technology that generates electricity without emitting carbon dioxide.”

Burning wood and trash emits more carbon dioxide per megawatt hour of electricity than coal, Freese said.

While wood, often referred to as “biomass,” today accounts for only about 2% of Minnesota’s energy, Freese said she thinks there is a significant chance that new biomass facilities would be built if the PUC allows burning wood under the new law.

“We know that Minnesota Power is planning to propose a facility that would burn wood,” she said.

While wood is often considered a renewable energy source, experts disagree about the net carbon impact. Some warn that it could encourage deforestation and ultimately increase greenhouse gas emissions.

Proponents argue that burning wood has a net carbon-neutral effect since trees planted to replace the harvested trees will absorb carbon emissions.

However, Freese said, the amount of additional tree plantings needed to overcome those emissions would take many decades to approach anything like carbon neutrality.

“We’re very concerned about biomass really taking off in this state in a way that actually increases our emissions,” Freese said.

Freese said she is also concerned about counting trash as a carbon-neutral fuel.

Proponents of municipal waste incineration say that it keeps trash out of landfills, which emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

But Freese said measuring methane emissions from landfills is difficult, so it is hard to know what the net effect is.

“By suggesting that [trash] incineration is carbon-free, just because maybe landfilling is worse,” she said, “really undermines our overall transition to get to net zero.”

“And of course, carbon-neutral isn’t what the law says,” Freese said. “It says carbon-free.”