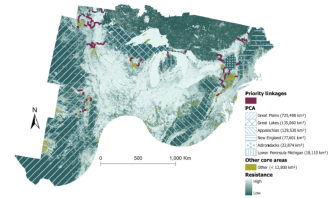

This map, from a 2022 paper by Merijn van den Bosch and colleagues, shows the six core areas identified in the study. Wolves currently occur only in the Great Lakes core area.

By Ruth Thornton

Gray wolves could thrive in the eastern United States well beyond their current range in the Great Lakes region, but they might have a hard time reaching other suitable habitats without human intervention, researchers say.

Wolves once had the largest known range of any land mammal but they were nearly exterminated in the United States in the early 1900s after persecution by humans.

Their population only recovered after they were placed under federal protection in the 1970s. They have since recolonized some areas where they once flourished, including in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

A 2022 study analyzed which areas in the eastern U.S. still have suitable habitat for wolves and are connected enough to each other so wolves might be able to travel between them.

To do that, the researchers used survey data collected between 2018 and 2020 by biologists working for the natural resource departments in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan.

They then modeled the characteristics of the habitats where wolves were found and predicted where else in the eastern U.S. large tracts of suitable areas occur. They also modeled how connected to each other those areas are.

They found that six areas had good habitat and were large enough to sustain wolves, but the animals occur in only one of them, the western Great Lakes. The other areas are separated from each other by less wolf-friendly habitats, including agricultural and urban areas.

Gray wolves may have difficulties moving into new areas without human help. Credit: Gary Kramer, USFWS.

Jerrold Belant, a professor of wildlife biology at Michigan State University and one of the co-authors of the study, said not all of these barriers are impossible for wolves to cross.

“The longer or wider that distance is, and the less suitable [for wolves] that is, the less likely the wolf is to cross it,” he said. “It doesn’t mean wolves won’t cross it or can’t cross it, it just is less likely.”

The other areas the study identified as suitable habitat were in the Great Plains, Appalachian Mountains, Adirondacks, New England and the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

“But for a wolf to get from upper Michigan or Wisconsin all the way there, that’s tricky with all the highways, all the cities, all the agricultural zones,” said Merijn van den Bosch, a wildlife ecologist with Colorado State University who co-authored the study while a graduate student at Michigan State University. “It’s tough.”

Crossing the Straits of Mackinac between Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsulas, for example, is tricky for wolves.

“Wolves can swim, and they can swim pretty well,” van den Bosch said. “During ice-over they can cross the straits relatively easily.”

The straits don’t always ice over, however. And when they do, shipping traffic usually breaks the ice up quickly, he said.

“Wolves have made it to the Lower Peninsula a couple of times,” he said, but not often enough to establish a population.

It’s not just the barriers between suitable habitats that might prevent wolves from expanding their current range, but also the human populations in and around those areas.

“Humans kind of ultimately decide where wolves are and where they are not,” he said. “Most wolf mortality is human-caused.”

Wolves have been protected under the federal Endangered Species Act since the 1970s and have since partially recovered, Belant said.

Many people therefore argue that they don’t need to be protected anymore.

But delisting them is not that simple.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has tried to delist the gray wolf several times, only to be sued by conservation groups. Courts have sided with the conservation groups, ordering the wolf to be listed again.

The confusion comes from the wording of the Endangered Species Act, which defines an endangered species as “any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.”

What exactly is considered a “significant portion” is not clear.

“Some of the more recent debates have been centered around how much of the range is occupied,” Belant said. “And part of that centers around historical range.”

About two-thirds of former wolf habitat in the eastern U.S. is no longer suitable for them because of human development and agriculture, he said. According to Belant, today wolves occupy only about 4% of their historical range and about 12% of the current suitable range.

John Vucetich, a wildlife biology professor at Michigan Technological University, said “there is no question that wolves do fit the definition of endangered species as provided in the Endangered Species Act.”

If wolves are delisted, states could introduce wolf hunts again, and each state would probably end up managing wolves differently.

But, he said, it is not purely a biological question, but also an ethical one.

“Wolves are symbols of nature for many humans across millennia,” he said. “What people love and hate about nature.”

Wolves also occasionally kill livestock and pets. Many states, including Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, have programs that reimburse livestock owners for the value of any animals wolves kill.

Vucetich said that we live in a world where we’re losing a sense of what it means to conserve nature.

“There are so many competing values, there’s human interests that are maybe a little separate from nature’s interests, and they often compete,” he said. “And so when does one prevail over the other?”