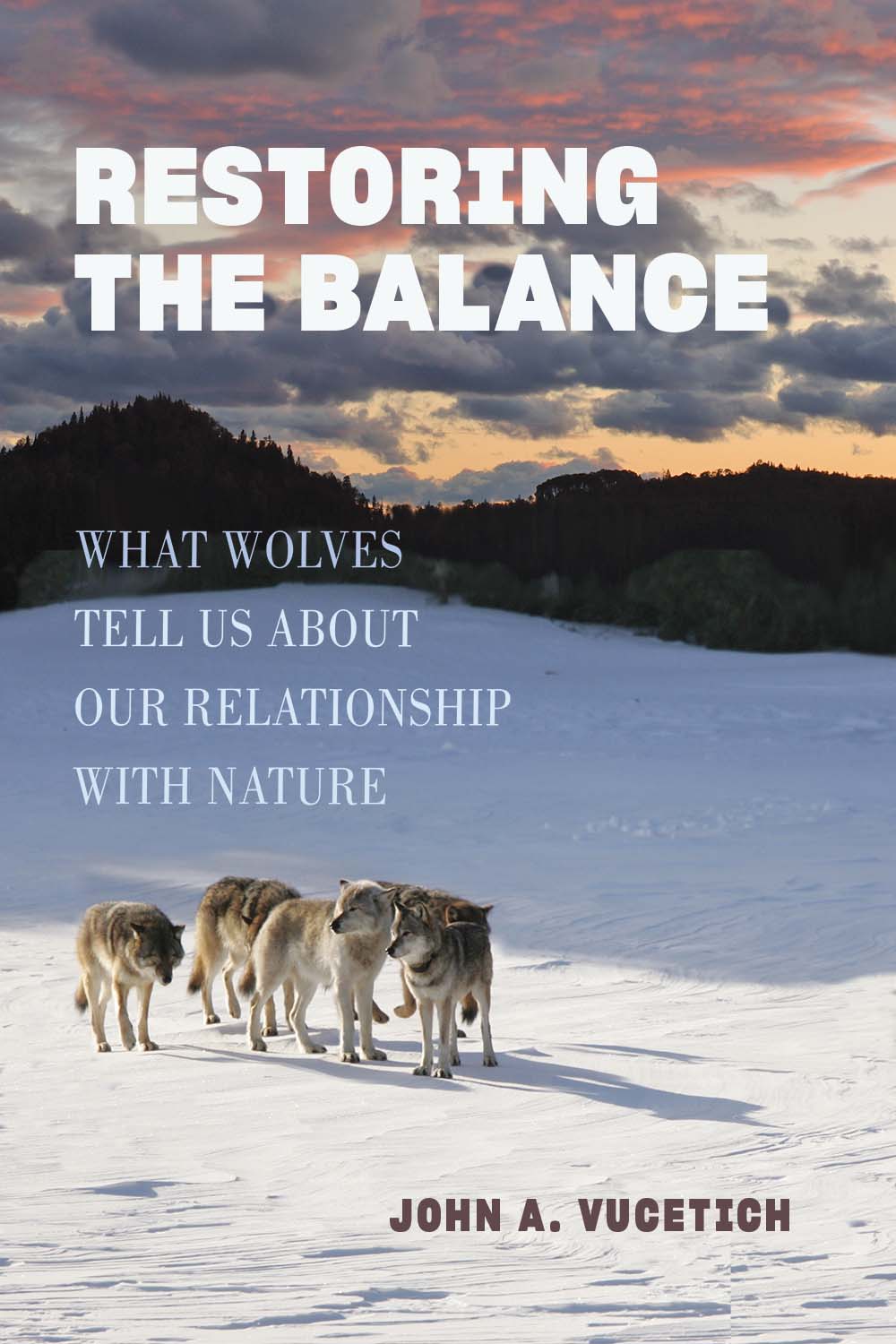

Cover of “Restoring the Balance: What Wolves Tell Us about Our Relationship with Nature” by John Vucetich

By Rachel Duckett

Over 20 years ago, John Vucetich watched a moose on Isle Royale and thought, “I wonder what that moose is thinking?”

He had absolutely no idea.

Vucetich, a professor of wildlife ecology at Michigan Tech University, began his work on Isle Royale as a freshman at the same university. Now 50, the Michigan native has studied wolves and moose for over 20 years on the pristine, isolated island in Lake Superior. He now leads the island National Park’s wolf-moose project.

“It’s probably fair to say that wolves found me rather than me having found them,” he said.

While the tracking technology and wolf politics have changed during his career, the nature of the work hasn’t.

“It’s a story that just unfolds one year at a time and there’s only one way to turn the page in the story,” he said. “And that’s to just wait and see how many wolves and moose there’ll be and then to try to figure out why.”

He shares that story in a recent book, Restoring the Balance: What Wolves Tell Us about Our Relationship with Nature (Johns Hopkins University Press, $49.95).

“I don’t think I know the right way for humans in nature to relate to one another,” Vucetich said. “But I do enjoy thinking about it broadly and openly and as deeply as I can.”

“And I like sharing those thoughts with others.”

The book combines natural history and memoir, much of it from his field notes and observations.

“A lot of memories and reflections build up over that kind of time. And they were starting to beat against the inside of the walls of my head,” he said. “And they needed to be let loose. And so I let them loose into this book.”

He details the behavior of wolves and moose and the larger lessons drawn from those observations.

“Towards the end of the book, I start to explore in a rather rich sort of way, the whole cause of wolves not doing well,” he said.

Lone wolves and the National Park Service

John Vucetich. Image: George Desort

Vucetich saw lsle Royale’s gray wolf population dwindle from as much as 50 in 1980 to near-extinction. About five years ago, only two remained.

The wolf decline caused the moose population to expand.

“Normally, the wolf population would have kept moose numbers lower,” he said. “But when the moose numbers got very high, they started to have adverse impacts on the vegetation.”

He also saw the controversial decision by the National Park Service to bring Canadian wolves to the island in 2019 to restore the ecosystem. It was a difficult decision as the Park Service’s philosophy is to preserve wilderness without human interference.

“Wolves are important to ecosystem health, and they belong in ecosystems like Isle Royale,” he said. “Their ecological function had been lost and so the Park Service was restoring that.”

Cam Sholly, the Midwest regional director of the National Park Service acknowledged the controversy in a 2018 press release: “We appreciate the intense public involvement throughout this process and look forward to continued outreach as this decision is implemented.”

The wolves on Isle Royale weren’t doing well because they were inbred and suffered from the impact of climate change. The warming climate reduced how often ice formed between the island and the mainland.

“For much of the time that wolves have been on Isle Royale, occasionally what would happen is a wolf would cross an ice bridge, and kind of rejuvenate the genetics of the population,” Vucetich said.

In the 1960s, ice bridges formed about three of every four years. In recent years, it’s about once every decade.

“The reason, of course, that ice bridges are less frequent is because of climate warming,” he said. “So it’s not so much that they were meddling with nature, it’s that they were mitigating something that humans had caused.”

To maintain the wolf population on Isle Royale, wildlife managers will likely have to bring one or two wolves from the mainland every 20 years, Vucetich said.

“In truth, what happened on Isle Royale is a concern for all of our national parks, really, because most or all of our national parks are threatened by climate change.”

Federal protection for the gray wolf

But the biggest threat to wolves in the Lower 48 states is hunting, Vucetich said.

“I think that we have learned in the last couple of years that there are powerful forces afoot that represent really nothing less than plain old hatred for wolves,” he said.

Gray wolves were delisted as an endangered species in 2020 after almost 45 years. Wolf hunting is now regulated by states.

Wolves have been hunted for several reasons, including potential harm to humans and livestock.

“My view on wolf hunting has been that you shouldn’t hunt wolves until a good reason has been presented for wanting to do so,” Vucetich said. “And the reasons that I’ve seen up until now are not good reasons to hunt wolves.”

Some people are pushing to restore federal protection.

But while hunting in some states may exacerbate the endangered status of wolves, the Endangered Species Act wasn’t designed to manage hunting. It was designed to prevent species from going extinct, Vucetich said.

Nonetheless, the gray wolf shouldn’t have been removed from the list to begin with, he said.

“The Endangered Species Act really clearly indicates that a species should be widely distributed throughout its former range before it can be delisted. Wolves in the Lower 48 occupy only about 15% of their former range.

Restoring the balance

Vucetich, a first-time author, explores the evolution of gray wolves on Isle Royale and the way that humans relate to them.

“I live my life with nature, interacting with nature, in some ways, just like everyone else does, just through the things that I use to sustain myself,” he said. “For human-nature relationships, I think the most common way to think of it is, ”Will it work?’”

However, the author said his work on Isle Royale—in particular, that experience he had with a moose early in his research career—changed the way he relates to nature.

“The thing that I enjoyed writing about the most in the book is a very particular event that led me to those thoughts,” he said. “And yeah, they changed my life in a way.”

While watching that moose long ago, he began to wonder, “What’s their experience?” That question became the primary way in which he viewed other animals.

“I had no idea what was happening between the ears of this moose,” he said. “How close can I come to figure that out a little bit as a scientist and a little bit as a person who joins that science with their imagination to try to better understand what their life is like?”

To Vucetich, the creatures on Earth count as people, not humans, but still people.

“They have interests,” he said. “They have an interest in what happens tomorrow, they have a memory of what happened yesterday. And they have an interest in being treated certain ways and not in other ways.”

He ponders the obligations that come with relationships between people.

“The one question that seems to frame the way I see it all is, “Is it fair?’” he said.

It is a challenging question.

“It’s hard to answer what counts as a fair relationship between two human beings and then you start asking, well, what looks like a fair relationship between humans and wolves?”

The book documents his “long inquiry” of fairness and his attempts to achieve it while providing a glimpse into the relatively untouched boreal forest of Isle Royale.

“The richest part is really, for me, just sharing it,” he said. “It feels like such a privilege to be in a position to see so many things about nature, things that other people care about, and that I’m the fella that’s fortunate enough to be able to share it with them.”

His favorite Isle Royale view is of the sky where it meets Lake Superior.

“It’s different every time you see it. It changes with the seasons and the lighting of the sun and the clouds.”

“And I’m just endlessly fascinated by that view.”