Image: The University of Wisconsin Press.

By Steven Maier

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula has been omitted from at least two maps of the country this past year.

When an online ticket marketplace left it off of an interactive map in June, a customer support representative joked on Facebook that they “got the important part of Michigan.”

A month later, Walmart forgot to include the peninsula in a graphic.

The snubs aren’t without precedent–a WhiteHouse.gov page did it in 2013. The peninsula was even omitted from a state tourism campaign graphic in the 1980s, said Kate Remlinger, a Grand Valley State University English professor.

It’s easy for Upper Peninsula residents to feel unappreciated. Two books published this summer attempt to set the record straight.

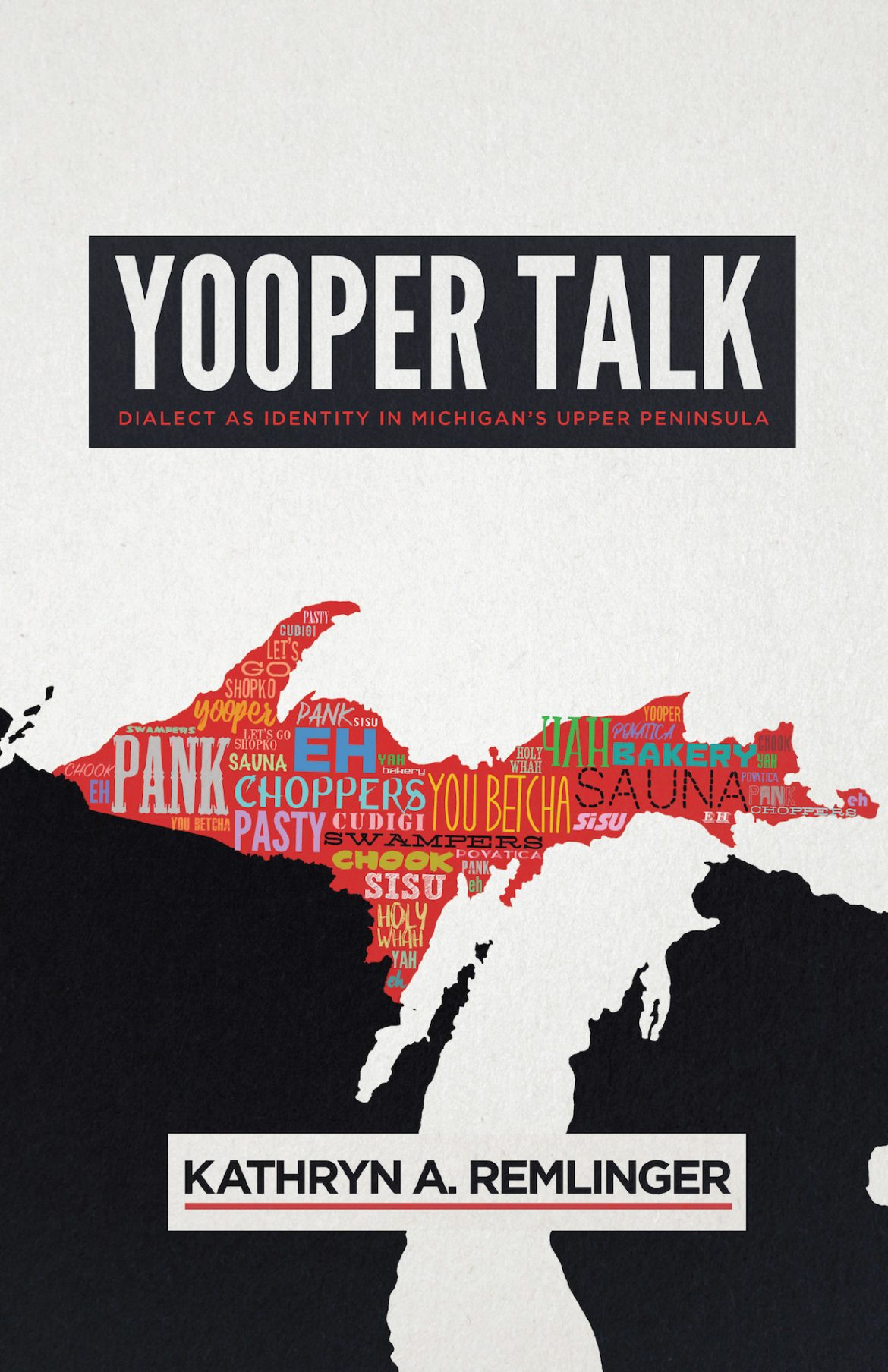

Remlinger’s newest book, “Yooper Talk, Dialect as Identity in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula,” is the synthesis of a two-decades study of a peninsula that’s been stigmatized in part because of how its people speak. It’s a dialectic concoction arising from the interactions of the native Ojibwe peoples, transplanted East Coast and Midwest residents and the British, Western and Central European, Scandinavian, Finnish, Russian and Chinese immigrants who settled there.

The dialect is mocked by some who associate it with the backwoods and backwardness, Remlinger said. Some students from the Upper Peninsula change their speech to avoid teasing, she said.

“If you want to find out which groups are stigmatized in a society, look at which dialects are stigmatized,” she said. “There’s a one-to-one correspondence.”

Kate Remlinger. Image: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Remlinger first visited the U.P. in the late 1990s as a graduate student in sociolinguistics at Michigan Technological University in Houghton. She began to talk to friends she met from the peninsula about how they talked differently from where she had lived in Kentucky and Ohio.

The book is a product of those and other conversations over the years–an exploration of the identity of the peninsula and the “Yoopers” who live there.

“I’m especially interested in identity and how people use dialect as kind of a badge of identity, of who they are,” she said.

Remlinger’s book explores U.P. identity with clarity, driven by anecdotes and historical accounts. She goes beyond speech analysis, providing enough narrative and peninsula history to engage readers lacking a linguistics background. “Yooper Talk” is available now from the University of Wisconsin Press for $24.95.

U.P. writing

Image: Michigan State University Press.

Another book published this summer celebrates the Upper Peninsula’s often-overlooked literature.

Ron Riekki grew up in the Upper Peninsula in Palmer and Negaunee, adjacent towns 15 miles southwest of Marquette. He’s now a successful author, poet, playwright, screenwriter and anthology collector. His newest anthology, “And Here: 100 Years of Upper Peninsula Writing, 1917-2017,” is partially a response to the lack of pride his educators showed in Upper Peninsula identity.

Someone once asked Riekki if he called himself a “Michigander,” or a “Michiganian.”

“My response was that I’m a Yooper,” he said. “And as a Yooper, I grew up with a strong sense of a lack of U.P. literature. As I grew older, I realized it existed; it just wasn’t taught in the schools.”

Local bookstores didn’t promote it, he said. Many Michigan anthologies left U.P. writers out. They might include men who wrote about the U.P., but many of them weren’t natives. There was almost no inclusion of classic peninsula writers like the acclaimed literary writer Bamewawagezhikaquay, also known as Jane Johnston Schoolcraft; an Ojibwe woman born in Sault Ste. Marie in 1800.

The anthology compiles short stories, poems and even the lyrics of Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” It includes established names like Ernest Hemingway, Steve Hamilton, Thomas Lynch and Emily Van Kley. And it contains local authors and poets.

Writers like Kathleen Heideman welcome the exposure. The anthology includes one of her poems, an excerpt from a series inspired by the brokenness she felt during interviews with the people of Negaunee, a former mining community. The mines are long dry, but ore can still be found scattered on the ground.

Heideman isn’t from the area–but she eventually moved there from Minnesota after she fell in love with the peninsula’s can-do spirit. She now lives in Marquette, on the coast of Lake Superior.

“When you fall in love with the Upper Peninsula,” she said, “you feel like you can’t live any other place in the world.”

This is Riekki’s third U.P. anthology–the first focused on new writings, and the second, published in 2015, featured U.P. women writers like Andrea Scarpino, a poet who moved to Marquette in 2010. Now the two are working on a Great Lakes anthology set to publish next year.

The U.P., Scarpino said, is not what people often think it is. Her family and friends thought she was moving to empty wilderness, not a town where the summers are filled with art shows.

“People always ask me, ‘what’s going on up there?’” Scarpino said. “And they’re surprised that we have such a vibrant writing community and artist community.”

Riekki wants his peninsula to be recognized for the things that set it apart, even from the other half of its own state–an identity that developed independently, largely separated from its southern sister until the Mackinac Bridge was opened in 1957.

“And Here” is available from the Michigan State University Press for $29.95.