An 11-year-old petition to protect the habitat of wintering populations of endangered Great Lakes’ piping plovers was rejected this month because it didn’t call the birds by their scientific names.

The petition was submitted in 2000 by a now-dead volunteer lawyer on behalf of the Alabama Audubon Council, Alabama Environmental Council and Alabama Ornithological Society. It requested that the birds be reclassified from threatened to endangered while wintering, and that critical wintering habitat be established for them.

Threatened means a species could become endangered; endangered means it is near extinction. Critical habitats are essential for an endangered or threatened species’ conservation and are more strictly protected.

Great Lakes piping plover. Photo: Michigan Department of Natural Resources

The petition was reviewed and rejected by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“We didn’t know what species or subspecies they were requesting action for,” said Lorna Patrick, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Whether it’s to list or delist, they must give us the scientific name of the species.”

That’s kind of hard to do now. The original petitioner is dead, and current officials with one of the organizations that are involved appear unaware of the effort. The Alabama Audubon Society and Ornithological Society have experienced “much turnover” since 2000, said Bianca Allen, administrative director for the Birmingham Audubon Society, and vice president of the Alabama Ornithological Society. She couldn’t find anyone with knowledge of the petition.

The Alabama Environmental Council did not return calls for comment. Great Lakes organizations, including Michigan Audubon, were unaware of the ruling and also had no comment.

Piping plovers nest on shorelines in the Great Lakes, the Great Plains states and along the Atlantic Coast. Starting in mid-summer, birds from all three areas migrate south along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, said Patty Kelly, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Most return to nesting areas by mid-May.

The Great Lakes population was listed as endangered in 1986; the other populations were listed as threatened the same year.

Federal officials are unclear as to what protection the petition sought. Great Lakes piping plovers are considered endangered regardless of where they are, Kelly said.

If accepted, the petition may have only affected the Great Lakes group by creating critical wintering habitat.

The U.S. Fisheries and Wildlife Services addressed the petition 11 years after it was submitted due to limited resources, Patrick said. The agency has corrected the problems that allowed the petition to fall through the cracks.

“Things were done different ten years ago,” Patrick said. “If we received this petition today, we would work with the groups to make sure that it was filled out correctly.”

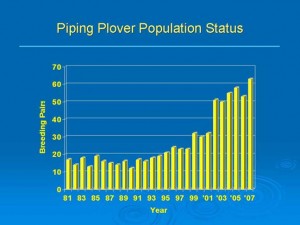

Piping plover breeding pairs have been rising in the Great Lakes region. Chart: Michigan Department of Natural Resources

Shoreline development and increases in human activity in nesting areas drove piping plovers to endangered status in the Great Lakes. Their future was looking ominous as breeding pairs hit a low of 12 in 1983.Conservation efforts in Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin have driven that number to over 60. Most wintering habitat for piping plovers is already on protected public lands, Kelly said. These include military bases, and state and federal parks.

And for the Great Lakes birds, which are often wearing colored bands for research and identification purposes, the news is even better, Kelly said.

“We have a lot of information that the Georgia coastline is preferred by birds (piping plovers) from the Great Lakes. It is one of the most protected coastlines we have.”

The petition also requested that the snowy plover, another small migratory bird from the Gulf and Pacific coasts, be switched from threatened to an endangered species. It was rejected on the same grounds.