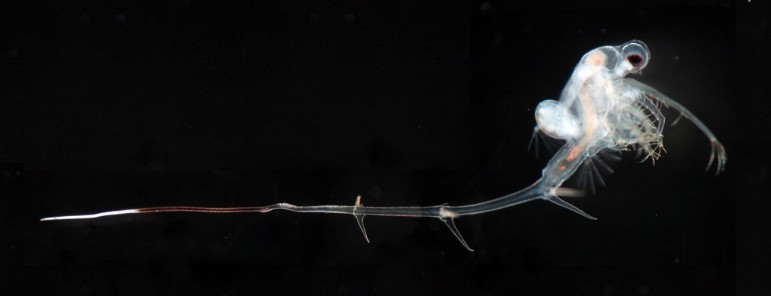

Spiny water flea. Image: Michigan State University

The self-sustaining populations of the spiny water flea, an invasive species, suggest a greater problem in the Great Lakes, according to researchers.

“They reflect a disruptive food web in the Great Lakes,” said Steven Pothoven, a research biologist stationed in Muskegon, Mich., for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Despite its misleading name, the spiny water flea is a crustacean rather than an insect. Its diet consists mostly of zooplankton. Small fish can’t eat the spiny water flea because of its long, barbed tail spine, but larger species of fish such as an adult paddlefish can do so.

In some of the Great Lakes, the invaders are the dominant predators. That’s a problem because they can eat the same food that small and young native fish eat.

Pothoven said it’s extremely hard for spiny water fleas to establish themselves in a healthy fish community because larger fish will eat them. That means bodies of water in which the spiny water flea thrives must already have problems, he said.

Recreational boaters are inadvertently moving spiny water fleas to inland lakes where they may have a larger impact on those small ecosystemsm Pothoven said.

The population of spiny water fleas in the Great Lakes hasn’t caused great ecological collapses in the lakes, Pothoven explained, but when combined with other problems in the area, there can be “cascading effects” yet to be seen by researchers.

The major result on the Great Lakes is a disrupted ecosystem, Pothoven said. These are “more difficult to manage and less predictable” than a healthy ecosystem, making it harder for scientists to address problems.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, transoceanic ships unknowingly introduced the spiny water flea, a native of Europe and Asia, to Lake Huron in 1984 via ballast water. By 1987, it was in all of the Great Lakes.

Recently, biologists found it in numerous inland bodies of water in both the U.S. and Canada.

The Allegheny River has a substantial population, according to a study published in BioInvasion Records. The river is close to Lake Erie.

David Argent and Derek Gray, researchers on the study and professors in the California University of Pennsylvania’s Biological and Environmental Sciences Department, said that it was probably introduced to the Allegheny River from boaters who had recently used the Great Lakes.

There has been a documented decrease of zooplankton in Harp Lake in Ontario as a result of the spiny water flea, which is “certain to have implications for regional species richness,” according to a study in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. The study is based on more than 50 years’ of data.

Since the health of the Great Lakes affects both the U.S. and Canada, the two countries signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1972. They amended the agreement in 2012 to include measures to prevent ecological harm, like the spiny water flea and other invasive species.

Pothoven said that the most significant measure taken in the U.S. to prevent its spread has been to educate boaters on boating hygiene.

Argent and Gray stressed the importance for boaters to clean the exterior of their boats, drain bilge water and allow fishing equipment to dry when moving among lakes and rivers because once spiny water fleas “are in a system and the conditions are conducive to survival, they not only expand their range but also thrive.”

In Ontario, volunteers from the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters, a nonprofit conservation organization, sample water from more than 100 inland lakes for the spiny water flea, said Alison Kirkpatrick, the monitoring and information specialist for the group.

Although the spiny water flea established itself in the Great Lakes more than 25 ago, the long-term effects of its feeding practices are yet to be determined.

“We need to further study the potential effects of shifting zooplankton communities” in the bodies of water where they live, Argent and Gray said.

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources recommends these measures to prevent the spiny water flea and other invasive species from spreading:

- Clean boats, trailers and other equipment thoroughly between fishing trips to keep from transporting undesirable fish pathogens and organisms from one water body to another.

- Allow boats, trailers and other equipment to fully dry for 4 to 6 hours in the sun before use.

- Don’t move fish or fish parts from one body of water to another.

- Don’t release live bait into any water body.

- Handle fish as gently as possible if you intend to release them and release them as quickly as possible.

- Don’t haul fish for long periods in live wells if you intend to release them.

- Report unusual numbers of dead or dying fish to the local DNR Fisheries Division office.

- Educate other anglers about the measure they can take to prevent the spread of fish diseases and other aquatic nuisance species.