Kat Kavanagh explains the Water Rangers web app. Image: Great Lakes Observing System

By Ian Wendrow

People can help keep their local lakes, rivers and streams healthier with a new app that just won its creators $5,000 in a Great Lakes data challenge.

The non-profit Ontario Water Rangers won the event put on by the Great Lakes Observing System (GLOS) to encourage the use of open source data either from GLOS or other water data collection services.

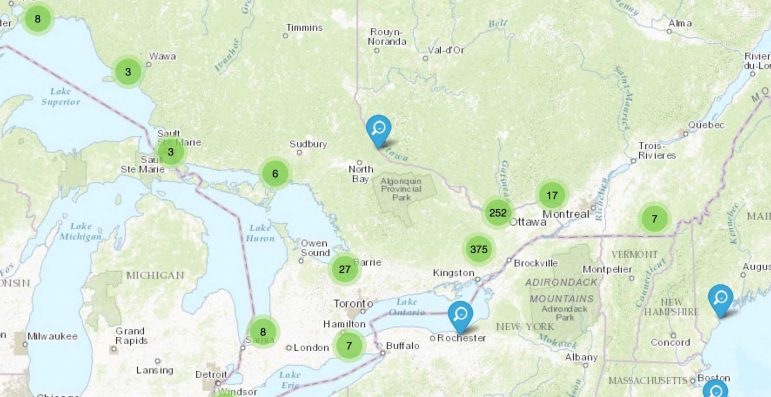

The app, found on the Water Rangers’ website, functions like a Google Map. Clicking on a dot zooms in to display small magnifying glasses. Users can then contribute observations including but not limited to wind speed, algae growth or invasive species and read a summary of past observations.

“We wanted to combine the data that we got from the Great Lakes Observing System and allow people to view the data in a simpler format and then they could contribute to that data point as well,” said Kat Kavanagh, a co-founder of the Water Rangers, which is a group that strives to use data and hands on outings to get people more involved with the water that surrounds them.

Broad view of the Water Rangers’ interactive web app.

Contestants were challenged to submit by August 15 ideas to make water related data readily available and useful for those living near the Great Lakes. Five groups submitted proposals.The Water Rangers was the only entry from Canada.

“We didn’t get as many submissions as we had hoped,” said Kristin Schrader, the communications manager for GLOS.

“But the entries we got were all phenomenal and we received a lot of support. The highest support we got came from Aquatics Informatics, which I think is an interesting example of private industry supporting a nonprofit in the pursuit of more and better data.”

This victory for Water Rangers is “a huge progression for us,” Kavanagh said. It’s also a culmination of a year and half of work, which began with Kavanagh’s desire to bridge the gap between data and citizens.

View of the web app’s summary screen. Users can upload their own observations here.

And it had a deeply personal connection for her.

“My dad was the person that did the phosphorous testing on our lake every year,” she said.

“He collected the data but he didn’t really understand it and he didn’t have a way to share it or to look at trends over time. That’s how Water Rangers got started.”

While the idea was planted by Kavanagh and her husband Ollie, it wouldn’t be until an Aqua Hacking convention that Water Rangers would begin in earnest.

Similar to the GLOS Data Challenge, Aqua Hacking is a “hackathon” event lasting a few days. Participants produce a prototype app to promote the health of Canadian regional waterways.

The very first Aqua Hacking took place just last year. It was here that Mark Dabrowski, a web developer and co-founder of Water Rangers, met Kavanagh.

“Over the past year I read a lot of books, watched quite a few TED talks and I kinda got this idea that I wanted to do something more with my life, a little bit more impactful, something of value,” Dabrowski said.

An avid fan of nature, Dabrowski regularly hikes near the many rivers criss crossing the Ottawa region. His passions for technology and nature is what drew him to the Aqua Hacking event, “kicking off the whole thing.”

It was also here that Water Rangers linked up with its first partner, Ottawa Riverkeepers.

“It was actually the Ottawa Riverkeepers who presented the problem themselves for the Aqua Hacking challenge,” Dabrowski said.

That problem was the lengthy process involved in collecting and sharing water data. The goal of the Aqua Hacking challenge was to find a way to make that process much simpler and more streamlined, which is how the Water Rangers map eventually came to be.

Following Water Ranger’s success, the Ottawa Riverkeepers became the primary beta testers of the app. Along the way the Water Rangers collaborated with other organizations like the Mobile Baykeepers, the Rideau Valley and Mississippi Valley Conservation Authority.

Originally the Water Rangers was named the River Rangers, focusing solely on rivers and streams. But working with these other groups helped Water Rangers realize the importance of covering all bodies of water.

“So that’s where we got the idea for doing more than just water quality tests, doing invasive species as well as wildlife and things like that,” Dabrowski said.

These partnerships work in a symbiotic way. While Water Rangers receives new ideas on what to monitor and how, they help provide technical expertise to other groups who may lack knowledge or resources.

The Water Rangers plan to use the prize money to continue work on the app. Further collaboration will strengthen existing features and find ways to make it more user friendly while still delivering hard data, said Kavanagh.

Even with the rapid growth and networking, it is the work that Water Rangers does with children that Kavanagh is most proud.

“One of the cool things is that it reconnects them with the water,” she said.

“One of the girls said to me, ‘I went to more beaches and I saw so many new places!’ But she also talked about how she picked up trash and felt a kindred desire to take care of these bodies of water.”

Thanks for featuring us! We really enjoyed working with GLOS, and look forward to lots more partnerships.