Editor’s note: This piece first appeared on Environmental Health News and is reprinted with permission.

By Brian Bienkowski

Environmental Health News

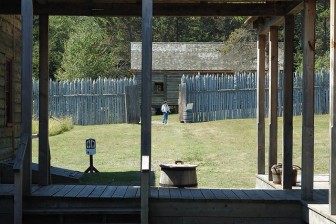

Grand Portage National Monument has reconstructed the fur trading depot from the 18th century. Researchers suspect a common trade item from that time might have left some contamination in the monument. Image: Joel Dinda/flickr

The Grand Portage National Monument is a former fur trading site full of conifers, wetlands and beaver dams — a history and landscape that may be behind the toxic mercury loads in the monument’s streams.

The national monument lies in the northeastern tip of Minnesota on the north shore of Lake Superior — not exactly where one would expect heavy pollution. But experts say the monument’s landscape and history may be a perfect mix for elemental mercury to accumulate and convert into its more toxic form — methylmercury, a contaminant that can impair developing brains and nervous systems in humans and wildlife.

Scientists say the monument has about the same level of mercury as other forests in the area — but the percentage that is methylmercury is much higher. For example, methylmercury accounts for more than 90 percent of the total mercury in dragonfly larvae from the streams, which is at the high end of what is commonly found in the region’s dragonflies.

The monument’s soil has an estimated 3 times more mercury per amount of organic carbon – which is what mercury binds to – than five other parks in the western Great Lakes region. More organic carbon generally means more mercury in soil, said Kristofer Rolfhus, a chemistry professor and researcher from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and lead author of the study detailing the monument’s contamination.

Mercury travels around the planet and today is mostly due to coal-fired plant emissions. But the monument has a unique history and set of challenges when it comes to mercury loads.

“We know it’s a very sensitive ecosystem,” said Brandon Seitz, a biological science technician with the National Park Service based at the Grand Portage National Monument. And Seitz and colleagues are starting to piece together why.

The monument is homage to the 18th century fur trade route of the Ojibwe people and the North West Company, headquartered in Montreal at the time. The route was a gateway to Canada where fur and international markets thrived.

Unfortunately one of the major trade items and gifts among traders along the Grand Portage route was vermilion, a synthetic mercury-containing pigment. U.S. Geologic Survey researchers found mercury levels in soils along the trade route were about 2 times higher than nearby soil off the route.

Another factor in the monument’s mercury sensitivity is the trees, Seitz said. It has a coniferous forest, and conifer trees “scour mercury from the air,” Seitz said. “That’s one thing we have going against us.”

Fishing is quite popular in Minnesota’s North Shore region. State officials found about 1 in 10 babies from the area have dangerous levels of mercury in them. Image: Randen Pederson/flickr

But there’s more — water chemistry, for example.

The tea-colored water of the monument’s streams have a lower pH (higher acidity) than other regional streams, and there are a lot of wetlands — both of which have been linked to enhanced methylmercury, the highly toxic compound result of inorganic mercury meeting anaerobic organisms. Such organisms are more plentiful in wetlands and acidic water compared to the clean, clear water of lakes and rivers nearby the monument, Seitz said.

Rolfhus and colleagues checked fish mercury levels to see how people and wildlife that eat them could be impacted.

Fish low in the food chain mostly had lower mercury concentrations than what is expected to harm their health or reproduction. But wildlife eating such fish could have impacts. Sixty-one percent of the fish from Grand Portage Creek, 97 percent from Poplar Creek and 84 percent from Snow Creek had mercury levels higher than what is considered safe to eat for kingfisher birds, which are highly sensitive to mercury.

And 23 percent of the fish in the three creeks had mercury levels exceeding what is considered to be safe for mink to eat.

It’s unclear if there are any population level wildlife impacts due to mercury, Rolfhus said.

The levels of mercury found in the fish are more likely to harm small wildlife than humans. But there is previous evidence that people who live in Minnesota’s North Shore area along Lake Superior, where the monument is located, are mercury contaminated.

Two years ago, researchers at the state’s Department of Health reported more than 1,400 babies in the region and found 1 in 10 were born with potentially dangerous levels of mercury in their bodies.

Pat McCann, a research scientist with the state’s Department of Health who led the research, said it’s unclear if the levels in the babies were higher than other populations in the Great Lakes region.

However, “people definitely seem to be eating a lot of fish,” in the North Shore area, she said.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Fish are a healthy food and McCann and colleagues are trying to reduce mercury exposure but still encourage fish eating.

“We want them to choose the fish lower in mercury,” she said. “For fish caught from Lake Superior … lake herring or cisco, whitefish, smaller salmon and lake trout, depending on how often they eat it.”

McCann and colleagues are enrolling women in the area for another mercury testing project and working to incorporate fish consumption advice as part of regional medical clinics’ communication to women.

As for Grand Portage National Monument, Rolfhus said they’re going to do more sampling later this year to get a better idea of mercury sources.

Brian Bienkowski is a former reporter for Great Lakes Echo.