Brien Bienkowski is a staff writer for Environmental Health News where this story was first published.

LELAND, Mich. — A midsummer overcast lifts as Lake Michigan changes from inky black to a deep blue-green. Ben Turschak bends over the rail of the boat, staring into the abyss in search of an exact spot.

“There it is, there it is,” Turschak says. He points to an underwater buoy used to mark a stash of underwater cameras and monitoring equipment 60 feet below the surface.

Graduate student Emily Tyner prepares for a chilly dive. Image: Brian Bienkowski

Turschak, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee graduate student, and his colleague Emily Tyner climb into bulky dry suits and strap on air tanks, masks and flippers, preparing for a plunge into the 60-degree water.

“I’m a little nervous, I haven’t dived here in two years. I’ve dived in the Caribbean and it’s just much harder here,” Tyner says. “This lake might as well be an ocean.”

Turschak leads Tyner down to the bottom. Ten minutes later they splash up, then climb back onto the boat and start unloading their bounty of water samples and a big bag of smelly green algae.

“That’s the most gobies we’ve seen,” Tyner says. The aggressive bottom-feeding fish with a voracious appetite, accidentally imported from Eurasia, has taken over the nearshore waters here.

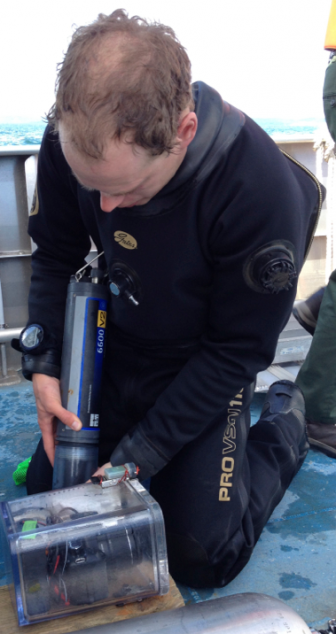

Graduate student Ben Turschak transfers water samples. Image: Brian Bienkowski

These dives in Good Harbor Bay — a cove just off a nationally protected shoreline and a hot spot for bird botulism die-offs — offer a peek into the bottom of the food web where round gobies, zebra mussels and other invaders have permanently altered the Great Lakes.

The algae, photos and water samples collected in these dives will be analyzed in an effort to understand the lake’s complex food webs. “It’s a whole new perspective on the bottom,” Tyner said.

The nonnative creatures have been driving a deadly surge in avian botulism in the Great Lakes over the past 15 years, killing an estimated 80,000 birds, including loons, ducks, gulls, cormorants and endangered piping plovers. Now scientists are searching for what has triggered this change in intensity of the disease: If they can unravel where and why the lethal toxin is building up in food webs, they can predict which shorelines are death traps for birds.

The botulism bacterium “is the most toxic natural substance on Earth. Just one gram could kill off like 2 million people,” said Stephen Riley, a fisheries biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. “And for these birds it’s essentially just widespread food poisoning.”

Invaders, rotting algae and dead birds

Outbreaks were first documented in the Great Lakes in the 1960s, but they ebbed and flowed until 1999, when they intensified on Lakes Erie, Huron, Ontario and Michigan.

It’s alarming how sustained it’s been over multiple years,” said Sue Jennings, a biologist and program manager with the National Park Service at Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes National Lakeshore. “With invasive species, lowering lake levels and higher water temperatures, we’ve just been moving away from natural processes.”

The toxin attacks birds’ nervous systems. “They’re unable to lift their wings up, they can’t open up their eyelids, their neck slumps over, which is called limberneck,” Jennings said. “Most often they’re out on the water and they drown from not being able to keep their head up.”

Some birds can recover if they haven’t ingested much of the toxin. But those badly affected appear to wander, slowly losing their ability to fly, even walk. They can die from lack of water, predation, drowning or respiratory failure.

A dead white-winged scoter on the shores of Lake Michigan apparently died from botulism. Image: Kayla Rizzo

The scene often is gruesome. In a span of a couple of weeks in October of 2012, nearly 300 birds — mostly loons — washed ashore at Sleeping Bear. The carcasses floated in nearshore waters and rotted on land, overwhelming Sleeping Bear’s small team of volunteers. The birds were stricken while stopping to eat on the Lake Michigan shore before wintering in the Chesapeake Bay or the Gulf of Mexico.

The outbreak was particularly distressing for the region’s bird lovers because one of the confirmed dead was a banded 21-year-old loon dubbed The Patriarch. The carnage continued for another month, with Sleeping Bear alone amassing about 1,400 dead loons in 2012.

Although botulism is a worldwide threat to birds, it’s found mostly in North America, where, over the last century, it has “killed many millions of birds, especially waterfowl and shorebirds, and was the most significant disease of waterbirds in total mortality,” according to one report. Lake Erie was the first Great Lake to get hit hard at the turn of the century, when an estimated 6,000 shorebirds died along its west basin.

It was 2006 when massive die-offs hit the unlikeliest of places: the Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes National Lakeshore. The 32 miles of nationally protected shoreline on Michigan’s Lower Peninsula has tree-dotted sand dunes and views of Lake Michigan and its offshore islands.

“That got our attention,” Jennings said. “By the years’ end we had over 3,000 birds that had washed ashore.”

While botulism is naturally occurring, type E outbreaks require a perfect storm of conditions: warm, oxygen-starved water and lots of dead plant matter.

Carried over from Eurasia in the ballast water of freighters, zebra and quagga mussels filter water for food, which increases water clarity and allows more sunlight through. This spurs growth of algae — often a type called cladophora. When the algae die and decay, oxygen is depleted and nutrients surge: the botulism toxin’s dream. The mussels also provide a hard surface for the cladophora to attach to. “So not only is it something to grow on, but the mussels excrete soluble phosphorous for the algae, so they’re providing it with fertilizer, too,” Riley said.

But how does the toxin then prey on birds?

Invasive round gobies are a major suspect in the avian botulism mystery.

Image: Petroglyph/flickr

It’s a puzzle of a food chain that scientists are still trying to unravel, said Harvey Bootsma, a researcher and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

“We’re pretty certain that birds are getting it from gobies. The question is, below gobies, how is it getting it into gobies?” Bootsma said. One suspect is bloodworms, which can live in low-oxygen environments.

Further complicating matters is botulism’s toxicity: It’s considered a bioterrorism concern, so researchers can’t just go out and grow it.

“We understand that there are weather, climate, and invasive species issues driving this whole thing but we can’t be everywhere and sample all the time,” said Brenda Lafrancois, an aquatic ecologist with the National Park Service based in Ashland, Wis. “Trying to find the toxin and pin its recent increases on one thing is like a needle in a haystack in that lake.”

Nevertheless, the bottom-feeding gobies are “a pretty big part of the equation,” she said. Just about every dead bird that tests positive for botulism has gobies in its stomach.

Zebra mussels have altered the bottom of the Great Lakes’ food web, creating ideal conditions for botulism. Image: Brian Bienkowski

Round gobies were first discovered in the St. Clair River — which drains Lake Huron into Lake St. Clair near Detroit — about 25 years ago, most likely via ships’ ballast water. Their populations have exploded across the basin.

“Their sheer numbers are just incredible. We don’t have native fish in those kind of densities,” Lafrancois said. ”If you’re a bird and you find 100 fish per meter of lake bottom, you’re going to hang out there a while.”

During fall feeding the loons dive deeper to eat than scientists had assumed.

“They were making deep dives of 40 to 45 meters [about 140 feet], it was a real eye opener,” said Kevin Kenow, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who tracked loons as they dived. “The speculation is that gobies move offshore in the fall, they feed on the quagga mussels at the bottom of the lake and the loons feed on them.”

Researchers know where to find gobies and what they eat, but the fish sometimes do weird things, including periodic feeding frenzies on sloughed algae mats. “It might be these kinds of unusual events that drive episodic botulism outbreaks,” Lafrancois said.

Lake Erie’s goby populations have dropped over the past decade, largely because they have more predators there than in Lake Michigan. As a result, outbreaks have slowed, Lafrancois said. Now Lake Michigan, where mussels and gobies remain ubiquitous, has become the focus of botulism research.

Botulism in paradise

Turschak and Tyner toss their scuba gear aside and catch their breath. Turschak starts uploading information into a computer that looks like it could withstand a bullet, while Tyner examines a bag of fluffy, decayed green algae with a scattering of mussel shells.

“We’re looking at temperature, depth, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, phytoplankton,” Turschak says. “And the cladophora bag will be tested for the botulism toxin.”

Researchers take cladophora samples from the lake. Image: Brian Bienkowski

Dan Ray, who leads the botulism monitoring program for the National Park Service at Sleeping Bear, hustles around to prep for the next plunge into Good Harbor Bay.

“During some of these outbreaks in past years we’d see a bunch of dead birds right here in this harbor, and nothing north or south along the shore,” Ray says. “That’s why we’re in this spot.”

Emily Tyner and Ben Turschak review data from the bottom of Lake Michigan.

After the massive die-off here in 2006, outbreaks continued: Officials reported that roughly 4,300 birds have died at Sleeping Bear since then.

“Basically we were getting calls coming in from people at their cottages, ‘we’ve never seen duck die-offs like this’,” said Mark Breederland, an extension educator for Michigan Sea Grant based in Traverse City.

It’s not just the amounts but also the types of birds that worry locals and scientists. The area is home to piping plovers, a small, stocky shorebird. An endangered species, the plover is a migratory bird that nests in the Great Lakes. Only about 70 pairs populate the region, with about 23 pairs in the Sleeping Bear National Lakeshore.

Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes is a federally protected shoreline. Image: Brian Bienkowski

Since 2007, eight piping plovers have died from botulism at Sleeping Bear. “With 140 or 150 birds total, even if you have one or two adults impacted by botulism, it could certainly have population impacts,” said Ethan Scott, the National Park Service’s piping plover recovery crew leader.

Plover populations already are skewed toward more males for unknown reasons, so “losing females could have an even great impact,” Scott said.

In addition, an estimated 794 common loons — with their shrill, haunting call and bright red eyes — have died from botulism at Sleeping Bear since 2007. About half of the United States’ population inhabits the Great Lakes from spring until late fall.

Scientists have found that low water levels and warm water are the two best predictors of outbreaks. Climate change models project a long-term decline in lake levels and an increase in lake temperatures.

But experts are predicting — and locals are praying for — a slow year for botulism. This year’s colder weather and higher water levels should stem some deaths, Jennings said.

When Turschak and Tyner took their dive trip that day in July, there had been no evidence of botulism yet for the season. But that changed the next day.

First clues of the summer

“Basically I wake up and walk down the beach every day,” says Kayla Rizzo as she walks barefoot on the beach. “It’s pretty great.”

But it’s not all a walk on the beach — there’s some detective work involved. An intern at the USGS, Rizzo collects water and soil samples at spots along the shoreline that have had bird die-offs in the past.

Bags, clipboards, tubes and other tools hang from her small frame. She also carries something she hopes she doesn’t have to use: a small, red shovel to bury dead birds.

Botulism kills gobies, too.

Image: Brian Bienkowski

While walking northward along the shore, avoiding sharp mussel shells, Rizzo and Shaun Miller, an interpretative park ranger, come across what looks like a pile of rotting feathers.

“Dead bird perhaps?” Miller asks, fumbling with the sooty clump in his latex-gloved hand.

“Maybe. You got a hunch?” Rizzo says.

“I got a hunch,” Miller says.

Botulism deaths usually pick up in September and October when mats of cladophora start washing ashore. But over the past decade, bird deaths have started by the beginning of July.

Rizzo said she’s seen more and more dead gobies while walking different sections of the Lake Michigan shoreline in July. It’s not clear what they died from, but botulism is toxic to gobies as well as birds.

Just hours after walking with Miller and making notes on dead fish, Rizzo had to use her shovel when she came across a dead white-winged scoter too deteriorated to be tested for botulism.

Kayla Rizzo of the USGS takes water samples on Lake Michigan’s shore. Image: Brian Bienkowski

Later that day there was even stronger evidence that botulism had appeared for the first time this season: A gull on North Manitou Island and another on the Platte River had been stumbling around, unable to fly.

Three birds, three different locations. And so it began.

“There’s just not much we can do,” Jennings said. “We monitor the shoreline and ask visitors to not touch any dead birds, and to report them.”

Volunteers walk miles along the shore and report cases of sick and dead birds to the National Park Service. Only a small number of dead birds can be tested. “Scavengers usually pick them apart,” Breederland said.

And that’s another worry: Botulism’s toxic trail doesn’t end at birds.

Shaun Miller of the National Park Service examines a pile of feathers. Image: Brian Bienkowski

While birds have been the most obvious casualties, there are still concerns about other wildlife, said Kevin Skerl, chief of natural resources for the National Park Service at Sleeping Bear.

“Small mammals, scavengers might, if they get sick, go off and hide somewhere,” he said. “They don’t just die on the beach or out in the water where we could see them …We just sort of crested the bird issue. But there are probably other food web impacts beyond the shore and the dead birds.”

And there are the other animals that heavily migrate to the shoreline in warm months: humans. Botulism can attack nerves, resulting in paralysis, and be deadly if not caught in time.

The Great Lakes — especially Ontario, Erie and Michigan — mostly have suffered from type C and E botulism. While type A and B are the ones people can contract from inadequately canned foods, they can be sickened by type E as well.

Jennings said experts aren’t too concerned about human botulism outbreaks. After all, the toxin has been infecting Great Lakes birds for decades. However, people handling the birds or eating Great Lakes fish should take extra caution, she said, adding that dogs also could be at risk if they eat dead organisms along the beach.

No easy solutions

Trillions of mussels and gobies will not go away anytime soon.

Invasive mussels litter the shoreline of Lake Michigan. Image: Brian Bienkowski

“The lakes cover such a large area and it’s estimated that there are about 400 trillion mussels alone in Lake Michigan,” Riley said. “As of right now, I don’t see a practical way to ever get rid of them.”

Great Lakes states have taken steps to slow the spread of invasive species, such as requiring boats to be washed when traveling between lakes or rivers, said Seth Herbst, a fisheries biologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Additionally, federal laws and Great Lakes’ states laws mandate that ships carrying ballast water must take steps to avoid introducing more invasive species.

Lafrancois said goby populations should eventually stabilize, but it’s unclear how long it might take. Researchers reported in July that predator fish are increasingly targeting Lake Michigan gobies.

In the meantime, scientists are looking at ways to slow the outbreaks. Some ideas include fish poisons and seismic guns to control goby populations, reducing the amount of cladophora by controlling nutrients flowing into the lake and using the information they have collected on dives to predict when and where the outbreaks might occur.

“Parts of the puzzle, like warm conditions, invasive species, are really well-pieced together,” Lafrancois said. “We know what’s on the cover of the puzzle box — dead birds — but we don’t have all the pieces put together just yet.”

Follow Brian on Twitter.

More predators in lake Erie, fewer outbreaks? Lets do that.