Visitors to the harvest camp listen to Mel Gasper, camp manager from the Lac Courte Oreilles band, as he talks about the Penokee Range and the proposed iron mine. Photo: Ron Seely/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

By Ron Seely

Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

THE PENOKEE RANGE — The fight over the fate of a massive iron ore mine has moved this summer from the state Capitol in Madison to the forests of northwestern Wisconsin and the green, undulating ridges along which Gogebic Taconite wants to dig its 4½-mile-long pit.

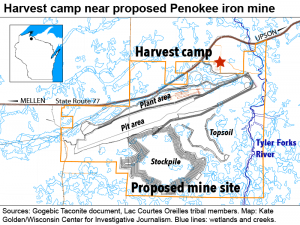

National and state news coverage of the mine has focused on a traditional Ojibwe encampment deep in the woods, about 30 miles southeast of Ashland, at the very edge of the proposed pit. From the rustic camp, started by members of the Lac Courte Oreilles Chippewa band, tribal members have launched what seems a cultural offensive — think fry bread, wild onions and birch bark baskets — to turn public opinion against the mine.

But organizers of the camp say it has an even deeper purpose.

Tribal officials and a treaty law expert say the Iron County camp, dubbed a harvest camp by Ojibwe, or Chippewa, lays the foundation for a possible legal case in which the tribe would invoke federal treaties.

Their goal: Block construction of the mine.

The camp and events surrounding it have inflamed what was already a volatile situation as Gogebic takes its first steps toward digging the iron ore pit. The state Department of Natural Resources is pressuring Iron County to take action against the camp, saying the county could lose the right to enforce forest regulations if it does not.

Criticism of the camp was immediate and harsh in mid-June after a group of masked protesters confronted mine workers at a test drilling site, shouting obscenities and death threats and ripping a camera from the hands of one of the workers. One of those protesters was charged with felony robbery.

Harvest camp organizers distanced themselves after that from the more radical mine opponents, turning in the protester who was eventually charged. In response to the confrontation, the mining company hired armed paramilitary-style guards who were later dismissed after it was discovered the Arizona security company they worked for was not licensed. Since then, the camp has been entirely peaceful, Iron County Sheriff Tony Furyk said.

But it still stirs anger among some mine supporters. The Iron County Board is scheduled to meet Tuesday to discuss a recommendation from its forestry committee that criminal and civil charges be filed against camp organizers for not having the appropriate permits.

State Sen. Tom Tiffany, R-Hazelhurst, who authored the bill clearing the way for the mine, also had little good to say about the camp. He called it a “squatters’ village,” even though tribal officials say they obtained approval from the county in May. That permit’s validity currently is in dispute.

“From what I’ve heard – I haven’t been there – there’s environmental damage being done with them building roads and trails. They’re interfering with other people’s ability to use the forest,” Tiffany said. “They’re destroying the very environment they claim they want to preserve.”

Hurley businessman Ross Peterson, who is also on the Iron County Mining Impact Committee, said he is not impressed by the camp. “To me it looks like a pile of junk, a bunch of tarps and barrels stacked all around,” said Peterson, a contractor, who has driven by the camp but not stopped to visit.

Peterson said he also has trouble understanding why some people are so against a project that would bring jobs to a county with double-digit unemployment.

Others, however, praise the camp for its peacefulness and for the insight it provides into the sensitive ecology of the Penokee Range. State Sen. Tim Cullen, D-Janesville, visited the camp recently. Cullen, who voted against the mining bill after trying to engineer a more environmentally friendly plan, disagreed with Tiffany’s assessment.

“I can report it isn’t at all what other people are saying,” Cullen said. “It’s peaceful. What it really is is an outdoor education lab. They’re making the case about the importance of the forest and the water to the band, to everyone, through history.”

Glenn Stoddard, a lawyer who represents the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, down river from the proposed mine, said the camp is a living demonstration of treaty rights, which include hunting, gathering and fishing.

“This all goes back to the reserved rights the tribes maintained in their treaties,” Stoddard said. “That’s exactly what the harvest camp is about. It’s an expression and an exercise of those rights.”

Tribal members say that, despite efforts to remove them, they will stay and invoke their off-reservation treaty rights.

They leave little doubt that the camp is a line in the sand.

“This is where they are going to mine,” said Mel Gasper, an elder from the Lac Courte Oreilles Chippewa band who is overseeing the camp and who spoke one late June afternoon as he prepared fry bread and other food for a communal dinner. “It would be right in the parking lot. What better place to pick a fight?”

The Chippewa have a powerful weapon — treaties negotiated in the mid-1800s by their forebears. Those treaties, Stoddard said, are more than dusty historical documents. They may soon come into play as Iron County challenges the legality of the camp.

Treaties survive challenge

The Chippewa signed treaties with the federal government in 1837 and 1842 in which they ceded land in about the northern third of Wisconsin in exchange for retaining rights to hunt, fish and gather wild rice and maple syrup on those lands. The rights were tested during a period of ugly, violent protest in the North Woods in the 1980s and early 1990s as the Chippewa began spearing walleye on lakes off their reservations.

That years-long controversy began with an act as simple as the construction of today’s Penokees camp. In 1974, two brothers, members of the Lac Courte Oreilles band were arrested for illegally spearing fish on Chief Lake, off the reservation.

Paul DeMain, the tribal member who came up with the idea for the harvest camp, recalled that the brothers, Fred and Mike Tribble, did not even spear a fish. “All they did was move that shack across that magic line,” DeMain said.

Tyler Forks River, which flows along the eastern border of the land where Gogebic Taconite wants to store mining wastes, empties downstream into the Bad River and Copper Falls State Park. Photo: Ron Seely/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

After the Tribbles were arrested, the Lac Courte Oreilles sued the state, arguing the arrests violated the treaties protecting tribal rights on all ceded lands.

Following years of courtroom battles, U.S. District Judge James Doyle, Sr. upheld off-reservation treaty rights in the landmark decision. The ruling was challenged by Wisconsin, sparking confrontations on boat landings each spring as the Chippewa took to the lakes to exercise their rights by spearing spawning walleye.

The protests frequently verged on violence, and law enforcement officers in riot gear from around the state were called to the northern landings to keep the peace. Eventually, the federal decision was upheld, the Chippewa continued spearing, and things quieted down in the North Woods.

Until now.

As was the case with spearing, Stoddard said an important first step in bringing the treaties to bear on the issue of mining is to actively exercise the rights. “Rights are always in danger of being lost if they aren’t exercised,” Stoddard said.

That was certainly true of off-reservation treaty rights for many years. For decades, tribal members were arrested and jailed for hunting on public lands off their reservations if they didn’t have a hunting license. Because of the spearfishing decisions, hunting, fishing and gathering off-reservation are now legal.

Now, Stoddard said, the harvest camp is helping make real the practices the treaties protect, including collecting food and natural medicines, from wild onions to mushrooms to maple syrup and tamarack bark.

Organizers of the camp also are inviting non-tribal members to visit so they can show them the wild Penokee landscape and the proposed mine site.

“Many people aren’t even aware of the treaties,” Stoddard said. “They haven’t been educated about them. Also, society has become much more urban so the activities covered by the treaties are foreign to people.

“The camp is intended to educate people about these things. It is one thing to be in a courtroom talking about the treaties. It is another to be out in the woods and see people exercising their rights. Then it makes sense to people.”

Stoddard said it is likely the treaties will come into play in an even more direct way. He said the mine could be challenged if potential environmental damage threatens to diminish the tribe’s ability to exercise its hunting, fishing and gathering rights.

And because the tribes are legally treated as sovereign nations, they can set tougher air and water standards – something the Bad River band has already done. Such standards came into play when Exxon Minerals tried to build a mine near Crandon upriver from some tribal rice beds. The proposal eventually died after two tribes used casino revenues to buy the mineral rights to the land in 2003.

Camping, communal meals

For all of the controversy surrounding the camp, it is a modest place. It is carved from dense woods just off a dirt road that continues to the rapids-filled Tyler Forks River, which runs along the eastern border of the 3,300 acres Gogebic Taconite has leased from Iron County for mining waste storage.

At the camp, an enormous canvas wall tent is stacked with tools, food and cooking supplies. Alongside the tent, lashed wooden frames hold pots and pans and dishes. Nearby is a tarp-covered, wooden frame structure that covers a fire circle. Numerous trails lead from the cook tent into the woods to other wood-frame, tarp lodges.

Gasper, squat and tough and talkative with his gray hair pulled back in a ponytail, runs the camp with a firm, kind hand. He greets visitors and invites them to sit in one of the many kitchen chairs outside the cook tent so that he can explain the camp and its purpose to them.

He pulls out maps to show the location of the proposed mine, pointing to rivers and wetlands and trails that he says date back centuries and were likely used by Native Americans to travel from the shores of Lake Superior up into the woods to seasonal camps.

The camp has been home to between four and 30 people a night. On weekends, dozens more, including many non-tribal members, visit the camp and walk to the mine site or the Tyler Forks River and the shadowy canyons of its upper reaches.

In the late afternoon, there is a communal meal of fry bread and venison or maybe bratwurst along with corn and fruit and sweets. At night there is often drumming and singing.

The camp also has hosted young people from other reservations so they can learn about traditional practices or hike in order to experience the Penokees first-hand.

“The reason I like having this camp here is because it expresses the spirit and lifestyle and culture of all the people in these hills, not just the tribal members but the loggers and the trappers,” Gasper said. “I hear their spirits at night. They want the land left as it is. They want this forest to be here.”

Camp draws non-tribal members

The camp also has meaning for non-tribal members.

Maureen Matusewic visits the camp often. She grew up in the area and spent much of her childhood roaming the Penokees with her father, who was a miner in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula until he was seriously injured in an accident.

For Matusewic, who opposes the proposed mine, the camp is a connection to the wild country of her youth and a means to learn more about the Chippewa. She said she values their quiet determination as well as their spiritual ties to the landscape.

State Sen. Bob Jauch, D-Poplar, who voted against the mining bill, has visited the camp twice.

“When I walked into the harvest camp, it brought history to life,” Jauch said. “There were kids chasing rabbits. There were people sitting around fires talking. I really felt the presence of the Native American ancestors who were up there 200 years ago.”

Gasper and others believe the camp has helped give some courage to speak out against the mine and has actually changed minds as people better understand the rich ecology of the Penokees.

“There is a huge shift going on right now,” Gasper said. “I think people are opening their ears. They’re listening.”

At least one official in Iron County, where support for the mine has been the strongest, has shifted his stance on the mine. Iron County Board member Jim Lambert said he was for the mine two years ago. But the more he has learned about the potential for environmental damage, the more skeptical he has become.

“I’m not a tree hugger,” Lambert said. “There’s rumors I’d shoot the last buffalo on earth. So I’m not a tree hugger. And I’m not against mining if it’s done properly… (But) I’ve asked a lot of questions. You have to understand what’s going to happen. There are going to be changes up there. What’s going to happen up there is that that country is going to be destroyed.”

Camp remains controversial

A spokesman for Gogebic Taconite said the camp is disruptive as protesters keep constant surveillance on company activities and hike to the mine site.

Mine guards on the site of the proposed Gogebic Taconite mine in Northwestern Wisconsin’s Penokee Range. Gogebic officials hired the armed guards from Bulletproof Security in Arizona. Photo: Rob Ganson

“We’re being watched by the people in the camp,” Bob Seitz said. “They come down in the middle of the night. It is an ongoing security risk.”

The state DNR also has become involved in the fate of the harvest camp. Joe Vairus, forest administrator for Iron County, said the forestry committee voted to seek enforcement against the camp partly because the DNR warned county officials they would have to take action or risk losing their right to enforce the County Forest Law.

Vairus said that law requires a permit for larger groups and a stay longer than two weeks – permission the camp organizers do not have. The law also requires the county to keep forest land open for public use, Vairus said. He contended the camp also is preventing public access.

“I bet you 90 to 95 percent of the people in Iron County are not wanting other people to occupy their forest,” Vairus said.

Quinn Williams, a state DNR lawyer, confirmed the agency has informed the county of its responsibilities under the County Forest Law but said it has not specifically suggested removal of the camp.

Said Stoddard: “What it says is that the camp is making the mining company and the interests that support mining nervous … It raises issues they don’t want to acknowledge. It raises the serious legal rights that Native American people have that mining supporters want to pretend don’t exist.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Pingback: Rosia Montana & Gogebic Taconite « Oneida Eye

“From what I’ve heard – I haven’t been there – there’s environmental damage being done with them building roads and trails. They’re interfering with other people’s ability to use the forest,” Tiffany said.

Are you kidding me?? Did he really have the gall to say this? Environmental damage from roads and trails? Has he for one nano-second thought about environmental damage from a 4,000 acre hole blown in the earth? (the answer is obviously no, and we shouldn’t expect him to)

Surprise! The white man’s discovered another way to keep his foot on the neck of First Peoples and exploit what little rights and resources with which the Anglo left Native Americans. Didn’t see that coming. Land, fish, casino revenue . . . Anglo politicos are like an octopus that keeps reaching into the Tribes’ pockets . . . smack one tentacle away, and it reaches for fishing rights. Smack that one away, and it tries to fish it’s way up the Indians’ pant leg to shake loose some gaming chips. Natives are an obstacle to the (Anglo) American way because even to HINT that there might be something more important, some OTHER motivating value, than storing up MONEY and POWER for yourself . . . well, that is as crazy as a rain dance.

What a joke: “The law also requires the county to keep forest land open for public use, Vairus said.”

So a camp is preventing the public from visiting…but I mine won’t? Give me a break.

Why is it that today’s Republicans are always on the side of environmental destruction? That was not always the case. I guess they don’t understand that being for “conservation” is really a “conservative” position.