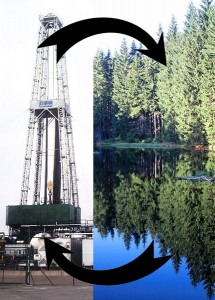

Oil rig photo and lake photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Editor’s note: This story was produced for Midwest Energy News and is reproduced in Great Lakes Echo under a creative commons license.

by Jeff Kart

A common method of extracting oil by injecting large amounts of water into old wells is coming under scrutiny by Michigan environmental groups.

The technique, known as water flooding, has been around for decades. But like many non-conventional means of oil recovery, it is becoming more economically viable as prices rise, and there is little information on exactly how much water is being traded for the oil that’s produced.

Energy extraction is placing increasing pressure on the nation’s water supply, according to a new report by the nonprofit New America Foundation.

The report, “The Water-Energy Nexus,” explains how traditional and alternative energy technologies are consuming a rising amount of water per unit of energy. While agriculture is responsible for 80 percent of water consumption in the United States, energy production consumes much of the remaining 20 percent.

“The competition between water and energy needs represents a critical business, security, and environmental issue, but it has not yet received the attention that it deserves,” Diana Glassman, one of the report’s authors, said in a statement.

A Michigan Example

Near Bay City, Michigan, Terry Miller heads up an environmental group called the Lone Tree Council, and also holds the elected position of Monitor Township trustee.

In the township, the Muskegon Development Co. is proposing a project torecover additional oil by flooding old wells with up to 42,000 gallons of water per day. The water usage would last for up to eight years, according to state records, for a total of more than 122 million gallons over the life of the project.

Muskegon Development has asked local officials to pay to extend a water line 2,300 feet for the work, to take place in what’s known as the Kawkawlin Field. The request has been tabled by township trustees, according to Miller, because it would cost the township an estimated $245,000.

The company proposed that the township would recoup the money through the sale of water back to Muskegon Development. The water would come from Lake Huron, via the Bay County Department of Water and Sewer. However, engineers for the township estimate it would take up to 9.5 years — longer than the projected life of the project — for the township to recoup its investment at the company’s estimated rate of water usage.

Representatives from Muskegon Development did not respond to requests for comment.

Like Glassman, Miller believes the impact of water use for energy extraction has fallen under the radar of government leaders and the general public. He sees secondary recovery as a practice that has bypassed laws like the international Great Lakes Compact, meant to protect the basin from large water withdrawals.

While the water amounts for the Kawkawlin project may seem large, they’re relatively small by industrial standards, and don’t meet the thresholds for extra regulations under the Compact, according to Hal Fitch, assistant supervisor of wells for the Michigan Office of Geological Survey.

Larry Organek, an engineer for the Michigan Office of Geological Survey, said the state Department of Environmental Quality isn’t keeping records of how much water is being used in total for the more than 50 secondary recovery projects currently in operation in the state.

Miller says that lack of oversight is exactly the problem.

“How many of these projects are going on, and how much nickel and diming of our water resources is occurring without anybody’s knowledge for the most part?” Miller said.

The Michigan Environmental Council, an umbrella group of more than 70 organizations in the state, shares Miller’s concerns about secondary recovery.

“The industry is pursuing riskier options like this because the easiest oil reserves have already been extracted,” said Energy Program Director David Gard.

“In a sense, we are getting more desperate to keep our gas tanks full. This means pressure to expand production from older wells will only intensify. We need to make sure this doesn’t happen at the cost of damaging our most precious natural resources.”

By the Numbers

U.S. oil production relies heavily on secondary recovery via water flooding, according to a 2009 report by Argonne National Laboratory.

The technique requires an average of 8 gallons of water for every 1 gallon of crude oil that’s recovered, although the amount needed can vary based on the geology and characteristics of individual wells.

In 2005, domestic onshore recovery operations in the U.S. required an estimated 1.2 billion gallons of injection water to produce 146 million gallons of conventional crude oil, according to the Argonne report. By comparison, U.S. agriculture uses about 100 billion gallons in a typical year.

The “Water-Energy Nexus” report, which was conducted by the World Policy Institute and EBG Capital, found that emerging oil and alternative fuel sources consume much more water than conventional oil.

For instance, petroleum from the Canadian oil sands extracted via surface mining techniques can consume 20 times more water than conventional oil drilling, and irrigated soy- and corn-based biofuels can require thousands of times more water than gasoline.

In addition, natural gas produced by hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” consumes seven times more water than conventional gas extraction, but roughly the same amount of water as conventional oil drilling.

Michigan regulators recently approved rules that will require fracking operations to report the amount of water they recover from wells.

Big Potential

According to an order granted by Fitch for the Muskegon Development work, there are 85 producing wells where the Kawkawlin project would take place, and more than 84,000 barrels of oil are left to be recovered using water injection.

“When you drill up a field, you might get 30 percent of the oil out of the reserve,” Fitch said, “so 70 percent is left behind. If you undertake secondary recovery, you can recover maybe another 20-25 percent.”

Secondary recovery using water has been going on in other parts of the Kawkawlin Field for about 15 years, according to Organek. The water line extension would allow for the third phase of the project.

Michigan regulators say the practice of secondary recovery using water has been growing in the state, or is at least becoming more economical, in the wake of $4-a-gallon gas prices, and crude oil prices above $100 a barrel.

“As the price of oil increases, these projects become more likely,” Organek said. “They are capital intensive in the beginning, but as with a lot of other projects, as the price of oil moves up, they become more economical.”

A state order filed for the project says Muskegon Development expects to generate a profit of around $16 per barrel during the first eight years. That’s based on spending $4.8 million for initial capital costs and about $11 million on operations during the eight-year period.

Most secondary recovery projects in Michigan are using water for oil recovery, Organek said. A half-dozen others use captured carbon dioxide, such as a project near Gaylord that’s part of the Midwest Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership.

Organek said he’s not aware of any environmental or safety violations related to past secondary recovery in the Kawkawlin Field. State and federal permits for such projects require periodic testing and inspections to prevent problems like leakage to groundwater.

Not for Drinking Anymore

A major concern about secondary recovery projects is that none of water is available again for drinking. State and federal permits for the Michigan project, for instance, don’t require the water to be treated once it becomes contaminated with crude oil.

Fitch acknowledges that water used for secondary recovery is “lost to the hydrologic cycle.”

“It is what we could call a consumptive use of water,” he said. “You have to balance that against the benefits of additional oil production.”

But if everything operates as planned, Fitch added, the water used remains in an underground formation, and there are protections in the law to guard against seepage that could contaminate groundwater.

“Theoretically, if you had produced all the oil you could with secondary recovery, you could pump water back out and treat it,” Fitch said, “but the economics are just not there.”

Jeff Kart is a freelance writer based in Bay City, Michigan. He’s been covering the Great Lakes and environmental issues for more than 10 years.